I was once sitting with my dad while I was googling how far different things in the solar system are from Earth. He was looking for exact numbers, and very clearly became more interested in every new figure I shouted out. I felt so happy. the moon? On average, 238,855 miles (384,400 km). James Webb Space Telescope? Bump that up to about 1 million miles (1,609,344 km). the sun? 93 million miles (149,668,992 km). Neptune? 2.8 one billion Miles (4.5 billion km). “Well, wait until you hear about Voyager 1,” I finally said, assuming he knew what was coming. He wasn’t.

“NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is not in the solar system anymore,” she announced. “No, it’s more than 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers).” Away from us “And it’s going further as we speak.” I can’t quite remember his answer, but I do remember an expression of utter disbelief. There were immediate inquiries about how this could physically happen. There were bewildered laughter, and different ways of saying “cool.” Mostly, there was an infectious sense of awe, and thus, a new Voyager 1 fan was born.

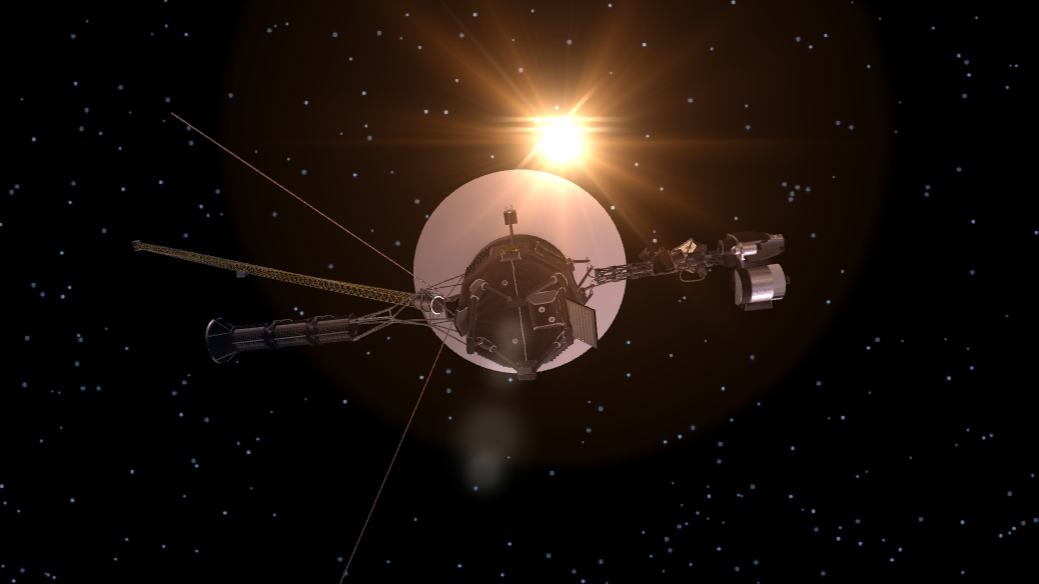

It’s easy to see why Voyager 1 is among our most beloved robotic space explorers — and thus easy to understand why so many people felt pain in their hearts several months ago, when Voyager 1 stopped talking to us.

Related: NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft finally calls home after 5 months of no contact

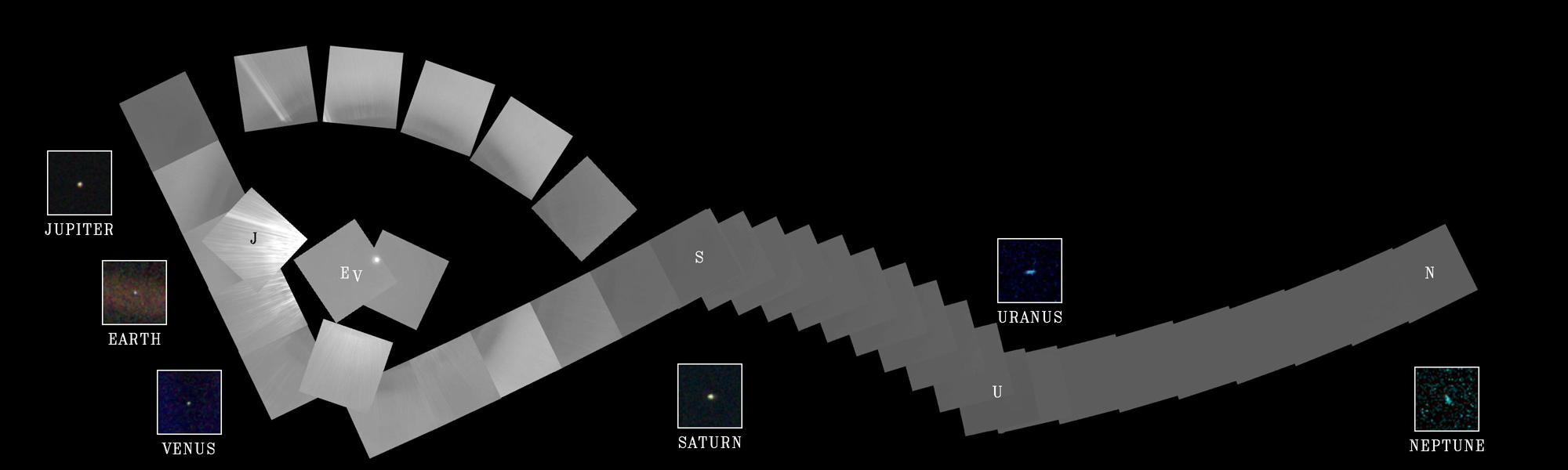

For reasons unknown at the time, this spacecraft was launched Send back gibberish Instead of the carefully structured, data-rich zeros and ones it has been providing ever since Launched in 1977. It was this classic computer language that allowed Voyager 1 to speak to its creators while earning it the title of “the furthest human-made object.” It’s how the spacecraft transmitted the vital vision that led to the discovery of the new Jovian moons, and thanks to this kind of binary podcast, scientists incredibly identified a new ring of Saturn and created the first and only “family portrait” of the solar system. This code is, in essence, crucial to the Voyager 1 object itself.

Additionally, to make matters worse, the problem behind this glitch was related to the vehicle’s flight data system, the system that relays information about Voyager 1’s health so that scientists can correct any problems that may arise. Issues like this one. Furthermore, due to the enormous distance separating the spacecraft from its operators on Earth, it takes about 22.5 hours for a transmission to reach the spacecraft, and then 22.5 hours to receive the transmission back. Unfortunately, things weren’t looking good for a while, about five months, to be exact.

But then, on April 20, Voyager 1 He finally called home With 0 read and 1 unread.

“The team got together early one weekend morning to see if telemetry would come back,” Voyager flight team member Bob Rasmussen told Space.com. “It was nice to have everyone gathered in one place like this to share in the moment of knowing that our efforts were successful. Our cheers were to the intrepid spacecraft and to the companions who enabled its recovery.”

And then, On May 22Voyager scientists made a welcome announcement that the spacecraft has successfully resumed returning science data from two of its four instruments, the Plasma Wave Subsystem and the Magnetometer Instrument. They are now working to get the other two systems, the cosmic ray subsystem and the low-energy charged particle instrument, up and running again. Although there were technically six other instruments aboard Voyager, they had been out of service for some time.

Return

Rasmussen was actually a member of the Voyager team in the 1970s, working on the project as a computer engineer before leaving for other missions including Cassini, which launched the spacecraft that taught us almost everything we currently know about Saturn. However, he returned to Voyager in 2022 due to a separate mission-related dilemma, and has remained on the team ever since.

“There are many original people who were there when Voyager launched, or even before that, who were part of the flight team and the science team,” Linda Spilker, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who also worked on the Voyager mission, told Space.com. .com on the This Week from Space podcast on the TWiT Network. “It’s a real tribute to Voyager — the longevity of not only the spacecraft, but also the people on the team.”

To bring Voyager 1 back online, in somewhat cinematic fashion, the team devised a complex solution that prompted the FDS to send a copy of its memory back to Earth. Through that memory read, operators were able to discover the crux of the problem — corrupted code running across one chip — which was then remedied by another chip (honestly, Very interesting) Code modification process. On the day Voyager 1 finally spoke again, “You could have heard a pin drop in the room,” Spilker said. “It was very silent. Everyone was looking at the screen and waiting and watching.”

Of course, Spilker also brought some peanuts for the team to eat, but not just any peanuts. Lucky peanut.

It’s a long-standing tradition at Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) to have a peanut feast before major mission events like launches and milestones, as well as the potential resurrection of Voyager 1. seem In the 1960s, when the agency was trying to launch the Ranger 7 mission, which was intended to take pictures and collect data on the surface of the moon. Rangers 1 through 6 had all failed, so Ranger 7 was a big deal. As such, mission path engineer Dick Wallace brought plenty of peanuts for the team to eat and relax. The Ranger 7 was certainly a success, and as Wallace once said, “The rest is history.”

Voyager 1 needed some of those positive vibes.

“It’s been five months since we’ve had any information,” Spilker explained. So, in this room of silence, along with the sounds of eating peanuts, Voyager 1 operators sat in front of their system monitors, waiting.

“All of a sudden I started filling out data,” Spilker said. That’s when the programmers who had been staring at those screens in anticipation jumped out of their chairs and started cheering: “I think they were the happiest people in the room, and there was a sense of joy about Voyager 1 coming back.” “.

Ultimately, Rasmussen says the team was able to conclude that the failure may have occurred due to a combination of aging and radiation damage through which energetic particles in space bombarded the vehicle. That’s also why he thinks it wouldn’t be too surprising to see a similar failure happen in the future, since Voyager 1 is still wandering beyond the far reaches of our stellar neighborhood just like its twin spacecraft, Voyager 2.

Granted, the spacecraft hasn’t been fully repaired yet, but it’s nice to know that things are finally looking up, especially with the recent news that some of its science instruments are back on track. To say the least, Rasmussen asserts that anything the team has learned so far has been concerning. “We are confident that we understand the problem well, and we remain optimistic that everything will return to normal – but we also expect that this will not be the last,” he said.

In fact, Rasmussen explains, Voyager 1 operators became optimistic about the situation for the first time after identifying the root cause of the malfunction with certainty. He also emphasized that the team’s morale never dropped. “We knew from indirect evidence that we had a spacecraft that was mostly intact,” he said. “Saying goodbye was not on our minds.”

He continued: “Instead, we wanted to push for a solution as quickly as possible so that other issues that had been neglected for months could be addressed. We are now quietly moving toward this goal.”

The future of Voyager

It cannot be ignored that over the past few months, there has been an atmosphere of anxiety and fear throughout the public domain that Voyager 1 was slowly moving towards transmitting its final 0 and final 1. News headlines all over the internet, one written by And I am one of them, it carried a clear negative weight. I think this is because even if Voyager 2 could technically carry the interstellar torch after Voyager 1, the prospect of losing Voyager 1 seems like the prospect of losing a piece of history.

“We crossed this border called the Heliopolis Edge,” Spilker explained of the trip. “Voyager 1 crossed this boundary in 2012, and Voyager 2 crossed it in 2018 – and since then, it has been the first spacecraft ever to make direct measurements of the interstellar medium.” This medium mainly refers to the matter that fills the space between stars. In this case, that’s the space between other stars and our sun, which, although we don’t always think of it as a single star, is just another star in the universe. A drop in the cosmic ocean.

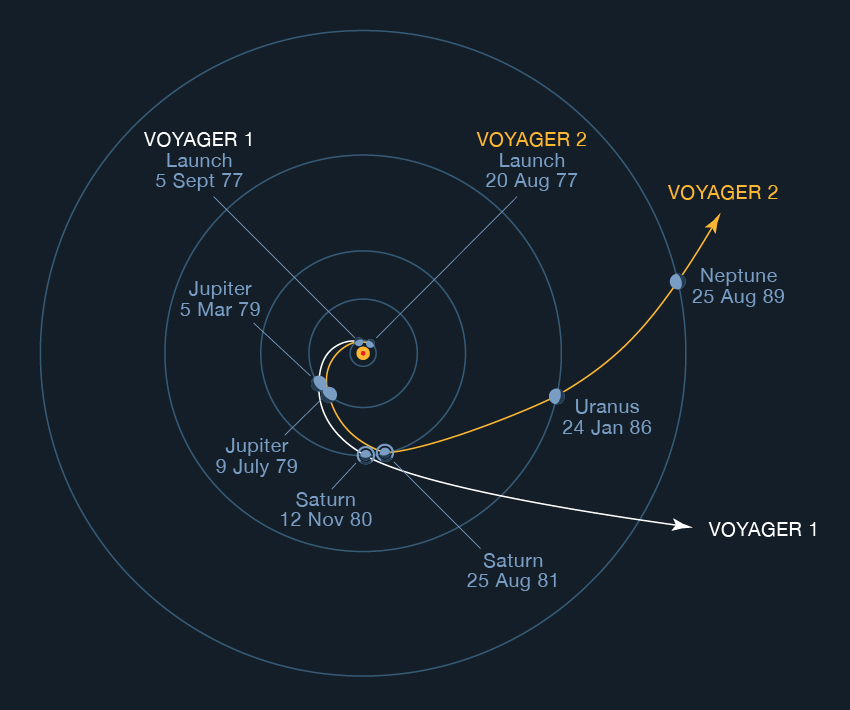

“JPL began building the two Voyager spacecraft in 1972,” Spilker explained. “For context, that was just three years after we made the first human walk on the moon — and the reason we started this early is because we had this rare alignment of the planets that happens once a year. 176 years old“It was this alignment that could promise checkpoints for spacecraft across the solar system, including Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. These checkpoints were important for the rovers in particular. Along with planetary visits come gravitational aids, and gravitational aids can help Gravity in flinging objects inside the solar system – and now we know what’s beyond that.

As the first man-made object to leave the solar system, as a relic of the early American space program, and as a testament to the power of decades-old technology, Voyager 1 has carved out the kind of legacy usually reserved for great things lost to time.

“Our scientists are eager to see what they’ve been missing,” Rasmussen said. “Everyone on the team is self-motivated by their commitment to this unique and important project. That’s where the real pressure comes from.”

However, in terms of energy, though, the team’s approach was decisive and resolute.

“No one was particularly excited or depressed,” he said. “We are confident that we can return to business as usual soon, but we also know that we are dealing with an aging spacecraft that is bound to have problems again in the future. This is just a fact of life on this mission, so it’s not worth worrying about.”

However, I imagine it will always please Voyager 1’s engineers to remember that this robotic explorer is occupying curious minds around the world. (Including my father’s mind now, thanks to me and Google.)

As Rasmussen says: “It’s great to know how much the world appreciates this mission.”

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”