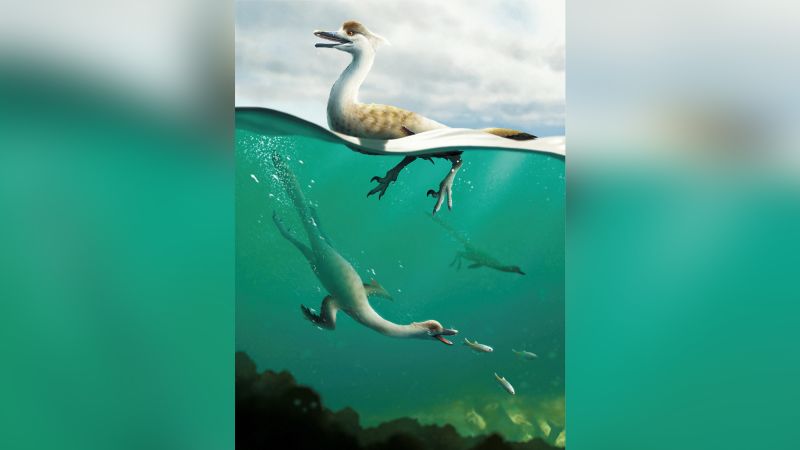

Reconstructing the lives of the Inalewites by Joshua Knoop. Credit: Joshua Knoop

An international team of scientists, including researchers from Germany and the United Kingdom, has described a new species of ancient marine crocodile, Enalioetes schroederi. Enalioetes lived in shallow seas that covered most of Germany during the Cretaceous period, about 135 million years ago.

This ancient crocodile was a member of the family Metriorhynchidae, a remarkable group that evolved a dolphin-like body plan. Metriorhynchids had smooth, scaleless skin, flippers, and a tail fin. They fed on a variety of prey, including fast-moving animals such as squid and fish, but some metriorhynchids had large, serrated teeth, suggesting they fed on other marine reptiles. Metriorhynchids were popular during the Jurassic, and their fossils became rare in the Cretaceous. Enalioetes schroederi is known from a three-dimensional skull, making it the best-preserved metriorhynchid known from the Cretaceous.

“This specimen is remarkable because it is one of the very few known marine crocodiles with a three-dimensionally preserved skull. This allowed us to examine the specimen with CT scans, and thus we were able to learn a lot about the internal anatomy of these marine crocodiles. This remarkable preservation allowed us to reconstruct the internal cavities and even the inner ear of the animal,” said Sven Sachs, from the Museum of Natural Sciences in Bielefeld and head of the project.

“Enalioetes gives us new insight into how metriorhynchids evolved during the Cretaceous,” explains Dr Mark Young from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Earth Sciences. “During the Jurassic, metriorhynchids evolved a body plan that was very different from other crocodilians – flippers, tail fins, loss of bony armour and smooth, scaleless skin. These changes were adaptations to an increasingly marine lifestyle. Enalioetes shows us that this trend continued into the Cretaceous, with Enalioetes’ eyes larger than other metriorhynchids (which were already large by crocodile standards) and its bony inner ear more compact than other metriorhynchids, a sign that Enalioetes was probably a faster swimmer.”

The perfectly preserved skull with the first cervical vertebrae was discovered over a hundred years ago by the German government architect Dr. Habke in a quarry in Sachsenhagen near Hanover. The specimen has an interesting history. It was given for preparation and study to Heinrich Schröder of the Prussian Geological Survey in Berlin where it was thought to have been incorporated into the collection. This led to the assumption that the specimen was lost during World War II. Later the specimen was rediscovered in the Minden Museum in West Germany. It turned out that the specimen had been returned to its discoverer, whose family brought it to Minden where they found a new home after World War II, taking the specimen with them. Since then, the crocodile has been one of the valuable specimens in the Minden collection.

The initial description was made by Henry Schröder of the Geological Survey in Berlin, and the species is named after him.

By comparing the fossil with those in other museum collections, Sachs and his team determined it was a species new to science.

For more information:

Sven Sachs et al., A new genus of meteoric crocodilians from the Lower Cretaceous of Germany, Journal of Systematic Paleontology (2024). DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2024.2359946

Martyrdom135-million-year-old marine crocodile sheds light on Cretaceous life (2024, August 9) Retrieved August 9, 2024 from https://phys.org/news/2024-08-million-year-marine-crocodile-cretaceous.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for private study or research purposes, no part of it may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”