NASA/AMES/JPL-Caltech/T. Pile

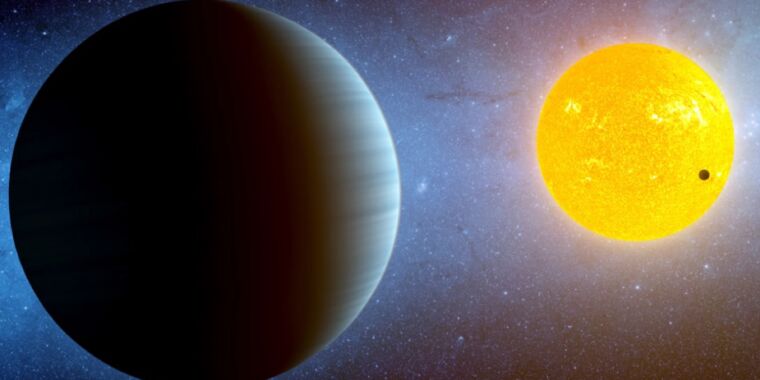

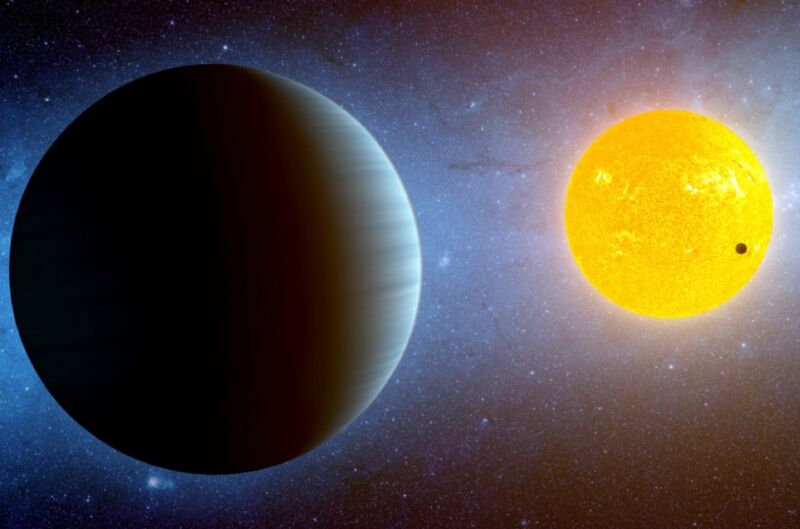

Astronomers have discovered an unusual Earth-sized exoplanet that they believe contains one hemisphere of molten lava, with the other half tidal locked in perpetual darkness. Co-authors and study leaders Benjamin Capestrant (University of Florida) and Melinda Soares-Furtado (University of Wisconsin-Madison) Provide details Yesterday at meeting of the American Astronomical Society in New Orleans. that Associated paper It was just published in the Astronomical Journal. last paper Published today in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics by a different group describe the discovery of a small, cold exoplanet with a massive exoplanet 100 times the mass of Jupiter.

As mentioned earlier, thanks to the huge array of exoplanets discovered by the Kepler mission, we now have a good idea of what types of planets are out there, where they orbit, and how common different types are. What we lack is a good sense of what that means in terms of conditions on the planets themselves. Kepler can tell us the size of a planet, but it doesn't know what the planet is made of. And planets in the “habitable zone” around stars could be consistent with anything from blazing infernos to frozen rocks.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) was launched with the aim of helping us learn what exoplanets actually look like. TESS is designed to identify planets orbiting bright stars relatively close to Earth, conditions that should allow subsequent observations to learn about their compositions and perhaps the compositions of their atmospheres.

Kepler and TESS identify planets using what's called the transit method. This applies to systems in which planets orbit in a plane that takes them between their host star and Earth. While this is happening, the planet blocks a small portion of the starlight we see from Earth (or nearby orbits). If these dips in light occur regularly, they indicate that there is something orbiting the star.

This tells us something about the planet. The frequency of dips in a star's light tells us how long it takes to orbit, which tells us how far a planet is from its host star. This, in addition to the brightness of the host star, tells us how much incoming light the planet receives, which will affect its temperature. (The range of distances where temperatures correspond to liquid water is called the habitable zone.) We can use that, along with the amount of light blocked, to figure out the size of the planet.

But to truly understand other planets and their ability to support life, we need to understand what they are made of and what their atmospheres look like. Although TESS does not answer these questions, it is designed to find planets with other instruments that can answer them.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”