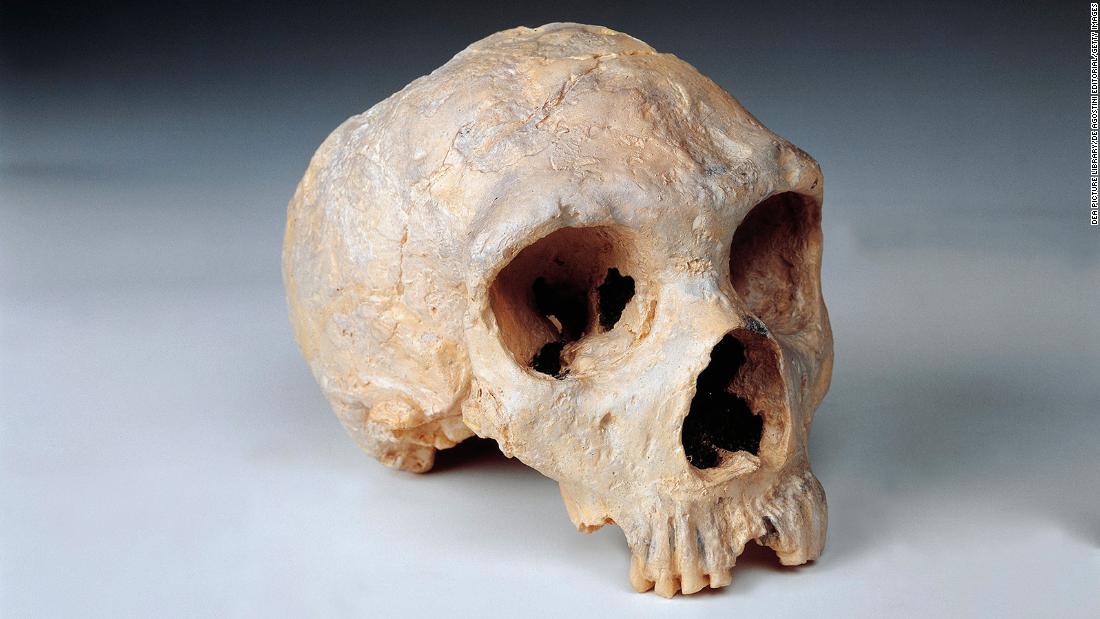

Now, an interesting study released on September 8 has revealed a possible difference that may have given modern humans, or Homo sapiens, a cognitive advantage over Neanderthals, the Stone Age hominids who lived in Europe and parts of Asia before their extinction about 40,000 years ago. .

Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Molecular Cell Biology and Genetics in Dresden, Germany, say they have identified a genetic mutation that led to faster formation of neurons in the brain of Homo sapiens. The primitive variant of the gene in question, known as TKTL1, differs from the modern human variant by a single amino acid.

“We have identified a gene that contributes to making us human,” said study author Welland Huttner, professor and director emeritus at the institute.

When two copies of the gene were inserted into mouse embryos, the research team found that a modern human variant of the gene led to an increase in a specific type of cell that creates neurons in the neocortex region of the brain. The scientists also tested the two genetic variants in rodent embryos and lab-grown brain tissue made from human stem cells, called organoids, with similar results.

The team concluded that this ability to produce more neurons likely gave Homo sapiens a cognitive advantage unrelated to overall brain size, suggesting that modern humans had “more neocortex to work with than ancient Neanderthals,” according to the study. published in the journal Science.

“This shows us that although we don’t know how many neurons a Neanderthal brain has, we can assume that modern humans have a higher number of neurons in the frontal lobe of the brain, where TKTL1 activity is higher than that of Neanderthals,” Huttner explains.

He added, “There has been debate about whether or not the frontal lobe of Neanderthals was as large as modern humans.”

“But we don’t need to care because (from this research) we know that modern humans should have more neurons in the frontal lobe…and we think that’s an advantage of cognitive abilities.”

‘Premature’ discovery

Alison Muotri, professor and director of the Stem Cell Program and Archeology Center at the University of California San Diego, said that while animal experiments revealed a “significant difference” in neuron production, the difference was more subtle in organelles. He did not participate in the research.

“This was only done in one cell line, and since we have so much versatility with this protocol for brain organoids, it would be ideal to repeat the experiments with a second cell line,” he said by email.

It’s also possible that the ancient version of the TKTL1 gene was not unique to Neanderthals, Muotri noted. Most genomic databases have focused on Western Europeans, and humans in other parts of the world likely shared the Neanderthal version of this gene.

“I think it’s too early to suggest differences between Neanderthals and modern human cognition,” he said.

Study co-author and geneticist Svante Pääbo, director of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, pioneered efforts to extract, sequence and analyze ancient DNA from Neanderthal bones.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”