Canned salmon are the unlikely heroes of the occasional natural history museum in the back of the warehouse, preserving decades of Alaska's marine environment in brine and tin.

Parasites can tell us a lot about an ecosystem, because they are usually found in many species. But unless they cause some major problems for humans, we historically haven't paid much attention to them.

This is a problem for parasite ecologists, such as Natalie Mastic and Chelsea Wood of the University of Washington, who have been searching for a way to retrospectively track the effects of parasites on marine mammals in the Pacific Northwest.

So when Wood received a phone call from the Seattle Seafood Produce Association, asking if she would be interested in taking boxes of old, dusty, expired salmon cans — dating back to the 1970s — off their hands, her answer was, unequivocally, yes.

The cases had been set aside for decades as part of the Society's quality control process, but in the hands of ecologists, they have become an archive of excellently preserved specimens; Not from salmon, but from worms.

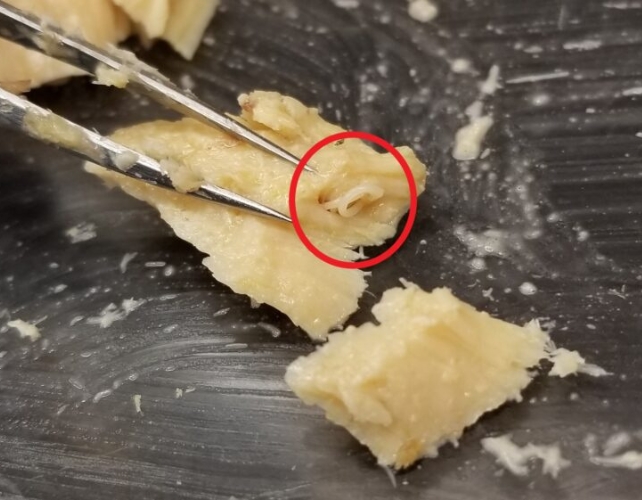

Although the idea of worms in canned fish is a bit alarming, these marine parasites are about 0.4 inches (1 cm) long. AnisakidsIt is harmless to humans when killed during the canning process.

“Everyone assumes that having worms in your salmon is a sign that things have gone off the rails.” He says wood.

“But the anisakid's life cycle integrates many components of the food web. I see their presence as a signal that the fish on your plate came from a healthy ecosystem.”

Anisakis enter the food web when they are ingested KrillWhich in turn are eaten by larger species. So they end up in the salmon and, eventually, in the intestines of marine mammals, where the worms complete their life cycle by reproducing. The mammals release their eggs into the ocean, starting the cycle again.

“If the host is not present — marine mammals, for example — the anisakis will not be able to complete their life cycle and their numbers will decline.” He says Wood, senior author of the paper.

The 178 cans in the Archive contain four different species of salmon caught from the Gulf of Alaska and Bristol Bay over a 42-year period (1979-2021), including 42 cans of salmon. (Onchorinchus kita), 22 coho (Oncorynchus Kesoch), 62 pink (Oncorynchus Gorbusha), and 52 Ain al-Suki (Onchorinchus nerca).

Although the techniques used to preserve salmon do not preserve the worms in their original state, the researchers were able to dissect the fillets and count the number of worms per gram of salmon.

They found that worms increased over time in chum and pink salmon, but not in sockeye or coho.

“Seeing their numbers rise over time, as we did with pink salmon, suggests that these parasites were able to find all the suitable hosts and reproduce. This could indicate a stable or recovering ecosystem, with enough suitable hosts for the anisakis.” “,” He says Mastic, lead author of the paper.

But stable levels of anisakid in coho and sockeye are difficult to interpret, especially since the canning process has made it difficult to identify specific anisakid species.

“Although we are confident about our identity at the family level, we have not been able to recognize our identity [anisakids] We discovered it at the species level,” the authors He writes“So it is possible that parasites of growing species tend to infect pink and sockeye salmon, while parasites of sedentary species tend to infect coho and sockeye salmon.”

Mastic and his colleagues believe that this new approach – turning dusty old cans into an environmental archive – could fuel many scientific discoveries. Looks like they've opened a big can of worms.

This research was published in Environment and evolution.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”