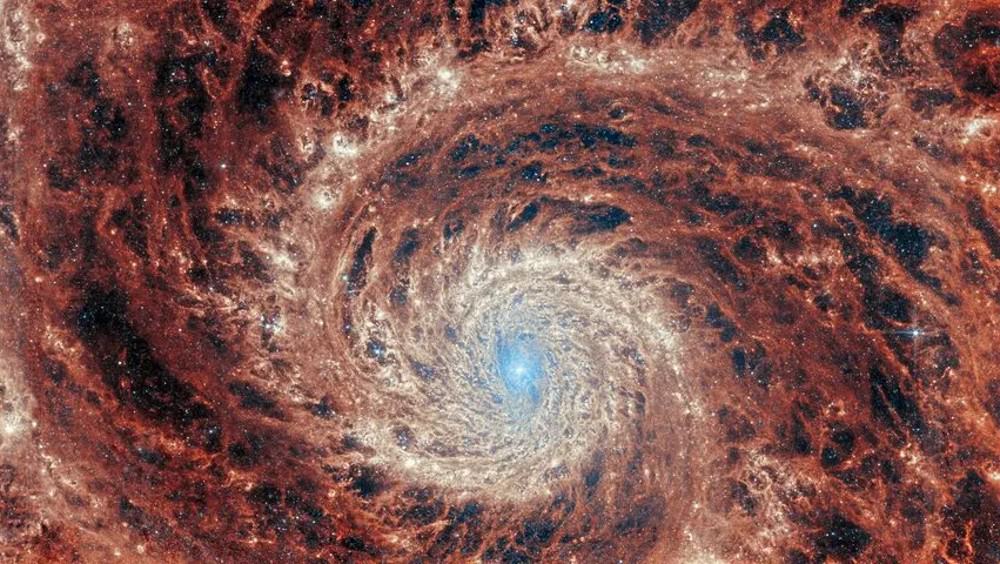

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, the largest and most powerful space telescope ever built, is now located nearly a million miles from Earth, pivoting from one spot of the sky to another while studying the target-rich environment that is our universe. It was the first bunch of photos Announced this week.

she’s amazing. It is also loaded with information about the universe, the interaction between galaxies and the birth and death of stars.

However, these images can be a mystery to the casual observer who lacks a degree in astrophysics. What are we looking at exactly?

Let’s take a closer look.

deep field

There are a lot of galaxies out there. This was the first image released to the public, demonstrating the telescope’s power in capturing the unusually faint infrared light emitted during the first billion years of the universe. The image is centered on a cluster of galaxies more than 4 billion light-years away, which means its light was emitted roughly when the Sun and Earth formed. Galaxies appear in the cluster as creamy white dots.

Together, these galaxies create a strong gravitational flexion in space that acts as a lens, magnifying and distorting distant objects. This results in mirror galaxies like the one in the upper right of the image that NASA astronomer Jane Rigby refers to as Laffy Taffy.

In another part of the image, the lens turned one galaxy into two mirror image galaxies.

Light comes in many wavelengths along the so-called electromagnetic spectrum. Humans see in a narrow band known as the “optical” part of the spectrum. The Webb telescope collects light emitted from infrared radiation – long wavelengths largely inaccessible to the Hubble telescope and completely invisible to us.

mosques

web

space

telescope

Sources: NASA; European Space Agency;

Space Telescope Science Institute

William Neve / The Washington Post

James Webb

space telescope

Sources: NASA; European Space Agency;

Space Telescope Science Institute

William Neve / The Washington Post

James Webb Space Telescope

Sources: NASA; European Space Agency; Space Telescope Science Institute

William Neve / The Washington Post

Webb’s team has scanned dozens of redder – and farthest – galaxies in this image, and determined that one of them – a small dotted dot – beamed its light about 13.1 billion years ago, just 700 million years after the Big Bang. (Distances to such objects are inferred by their “redshift”—how far the light has been interrupted by the expansion of space itself.)

The telescope obtained a spectrum of the galaxy, showing signs of oxygen, hydrogen and neon. This kind of observation, Rigby said, would explain what was happening during the first billion years of the universe: “We don’t know at all how big these galaxies are, and how many are out there.”

Southern Ring Nebula

Stars like our sun are remarkably stable nuclear fusion reactors over billions of years. But even they are getting old. This image shows what happens when a star dies. It sheds matter in the midst of its pulsating death.

These clouds of gas and dust, including complex particles, are the raw material for stars and planets that haven’t yet formed.

NASA released two images, one in the near infrared (relatively close to the “visible” part of the spectrum), and one in the mid-infrared (farther along the spectrum).

In the near infrared, the material forms a ring of foamy gas and dust, with ionized hot gas dominating the central region. Light rays shoot through the holes in the outer ring.

Only one star is clearly visible in the center. But this is a binary system – two stars bound together by gravity.

In the mid-infrared, we see both. Dying weaker. The telescope reveals that it is covered in dust.

Our Sun will look similar to this star in 5 billion years, explained Klaus Pontopedan, Webb Project Scientist at the Space Telescope Science Institute.

“It’s the life cycle of stars,” Pontopedan said. “This is the end of this star, but it is the beginning of other stars and other planetary systems.”

The image includes an interesting slash on one shoulder that astronomers recognized was a distant galaxy. Although it is a huge three-dimensional structure with billions of stars, we look at its edge, as if we were watching a Frisbee spinning away from us.

Stephan quintet

The picture has a lot of universe in it.

There are stars from our galaxy – which means they are in the foreground, in cosmological terms.

Foreground stars are identifiable in all of Webb’s images by “diffraction spikes,” which are a make-over of the telescope’s design. The diffraction spikes on these images act as a watermark for the Webb Telescope.

In the middle distance is what appears to be a quintet of galaxies.

The one on the left is not part of the cluster but rather in the foreground, about 40 million light-years away.

The telescope can distinguish individual stars in the foreground galaxy.

Many of them age as “red giants” towards the end of their lives, with well-documented properties that help astronomers appreciate their true luminosity and distance from them. Such observations could improve the model that scientists use to estimate the distance to objects across vast expanses of space.

The other four galaxies are about 290 million light-years away. The two are merged. The gravitational interactions of galaxies sent streams of star-forming gas and dust into intergalactic space.

Remarkably, this image, like the “deep field”, contains countless galaxies scattered in the background. Look closely and you will see beautiful and very distant spiral galaxies not unlike our own Milky Way.

The large galaxy at the top has a supermassive and extremely active black hole in its core, feeding on its surroundings. The black hole itself does not emit light, but its gravitational field activates nearby gas, causing the atoms to smash into each other and generate enormous heat.

Rigby said that the accretion disk of this black hole is shining with the energy of 40 billion suns: “Black holes do not emit any light, but their accretion disks certainly do!”

Carina Nebula

Seems like a good place to hang out! Complete with a gorgeous starry sky. This nebula is a star nursery in our galaxy.

“What looks like a starry night sky is part of a huge bubble that has been carved out of the cloud by ultraviolet radiation and stellar winds from young, very massive and hot stars that have already formed,” astronomer Amaya Morrow Martin said from space. Telescope Science Institute.

Streams of ionized material flow towards the top of the frame.

Webb can see the shock waves from newly blazing stars forming within the cloud. Their environment is hostile, because the same process that erodes the cloud can stop star formation.

The Hubble Telescope had previously examined this part of the sprawling Carina Nebula, and Webb’s team knew that the precisely defined boundary between the dusty cloud and the “open sky” would create a fascinating image.

This is more than just beautiful space art, said Joseph DePasquale, part of the team that processed the images at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore.

“We knew, based on the Hubble image, that the landscape of this would have looked very much like a mountain range and the sky behind it. We knew it would be aesthetically impressive there,” DiPasqual said. “But there was also a lot going on in terms of physics. Webb could go deep into the clouds and reveal the mysteries of what’s going on.”

about this story

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”