Sign up for CNN's Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news of fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

—

Strange radio circuits in space have mystified astronomers since the cosmic objects were first discovered in 2019. Now, scientists think they may understand what forms these mysterious celestial structures, and the answer could provide insight into galaxy evolution.

Individual radio circuits, also known as ORCs, are so massive that entire galaxies lie at their centers, with objects extending hundreds of thousands of light-years across.

Our Milky Way Galaxy is 30 kiloparsecs across, and one kiloparsec equals 3,260 light-years. Individual radio circuits measure hundreds of kilometers. So far, only 11 have been discovered, and some of them are potential ORCs that have not been confirmed, according to the researchers.

Astronomers have come up with several theories to determine what might form space rings, including that they are the result of massive cosmic collisions. But a new study suggests that the circles are shells sculpted by powerful galactic winds created when massive stars explode.

Astronomers first discovered individual radio circuits using the SKA Pathfinder telescope, operated by Australia's national science agency CSIRO, or the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization.

The telescope can scan large parts of the sky to detect faint signals, allowing scientists to detect unusual objects.

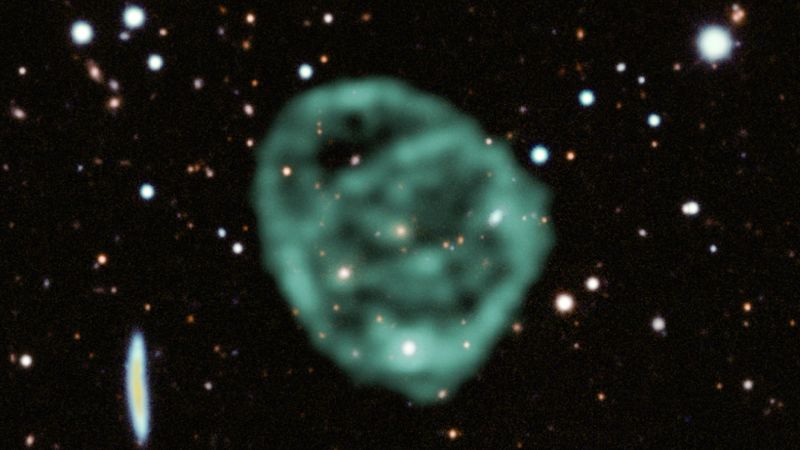

Researchers using the Radio Astronomy Observatory's MeerKAT telescope in South Africa also captured the first image of ORC, called ORC 1, in 2022. (MeerKat is short for Karoo Array Telescope, prefixed with the Afrikaans word for “more.”) The powerful telescope is Sensitive to dim radio light.

Theories poured in after the discovery of strange radio circuits: Perhaps those circuits were wormholes, the remains of black hole collisions, or powerful jets pumping out energetic particles, researchers hypothesized.

But before the new study, the circuits had only been observed through radio waves. Despite their enormous size, no visible-light, infrared, or X-ray telescopes have been able to detect individual radio circuits.

Alison Coyle, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California San Diego, and her collaborators decided to look more closely at ORC 4, the first known alien radio circuit observable from Earth's northern hemisphere. Coyle and her team studied ORC 4 using the W.M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaii, which revealed the presence of hot gas that is more luminous in visible light than seen in typical galaxies.

The result raised more questions.

Cowell became fascinated by strange radio circuits because she and her fellow researchers study massive “stellar galaxies,” which have a high rate of star formation. Galaxies can also propel rapidly flowing winds. When giant stars explode, they release gas into interstellar space, or the space between stars.

When enough stars explode at once, the force from the explosions can push gas out of the starburst galaxy at speeds of up to 4,473,873 miles per hour (2,000 kilometers per second).

“These galaxies are really interesting,” Cowell, the study’s lead author and chair of the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics at UC San Diego, said in a statement. “It occurs when two large galaxies collide. The merger pushes all the gas into a very small area, causing an intense explosion of star formation. Massive stars burn up quickly, and when they die they expel their gases in flowing winds.”

Cowell and her team thought that radio rings might be linked to stellar galaxies.

Using visible light and infrared data, Cowell's team calculated that the stars within the galaxy within ORC 4 are 6 billion years old.

“There was an explosion in star formation in this galaxy, but it ended about a billion years ago,” Cowell said.

Next, study co-author Cassandra Luchas, a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, ran simulations to recreate the size and properties of the radio circuit that included the amount of gas they detected using the Keck telescope.

Luchas's simulation showed that the flowing galactic winds blew for 200 million years before they stopped. Then, the forward shock wave continued to send the hot gas out of the galaxy, creating a radio circuit. Meanwhile, the reverse shock sent cooler gas into the galaxy.

These events occurred over an estimated 750 million years.

The new research was published in the journal nature It was presented at the 243rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in New Orleans on Monday.

“To make this work, you need a high-mass outflow rate, which means it's ejecting a lot of material very quickly. And the surrounding gas outside the galaxy must be low-density, otherwise the shock will stop. Those are the two main factors,” Coyle said. “It turns out.” The galaxies we were studying have high mass flow rates. It's rare, but it does exist. I really think this refers to ORCs created by some sort of flowing galactic wind.

Understanding the origins of individual radio circuits also ultimately helps astronomers understand the impact this phenomenon may have on the formation of galaxies over time.

“ORCs give us a way to see winds through radio data and spectroscopy,” Cowell said. “This can help us determine how common these intensely flowing galactic winds are and what the life cycle of the wind is. They can also help us learn more about galaxy evolution: Do all massive galaxies go through an ORC phase? Do spiral galaxies turn into ellipsoids when they stop forming stars?” ?I think there is a lot we can learn about ORCs and learn from ORCs.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”