Astronomers may have solved the mystery of how some of the brightest and hottest stars in the universe are born.

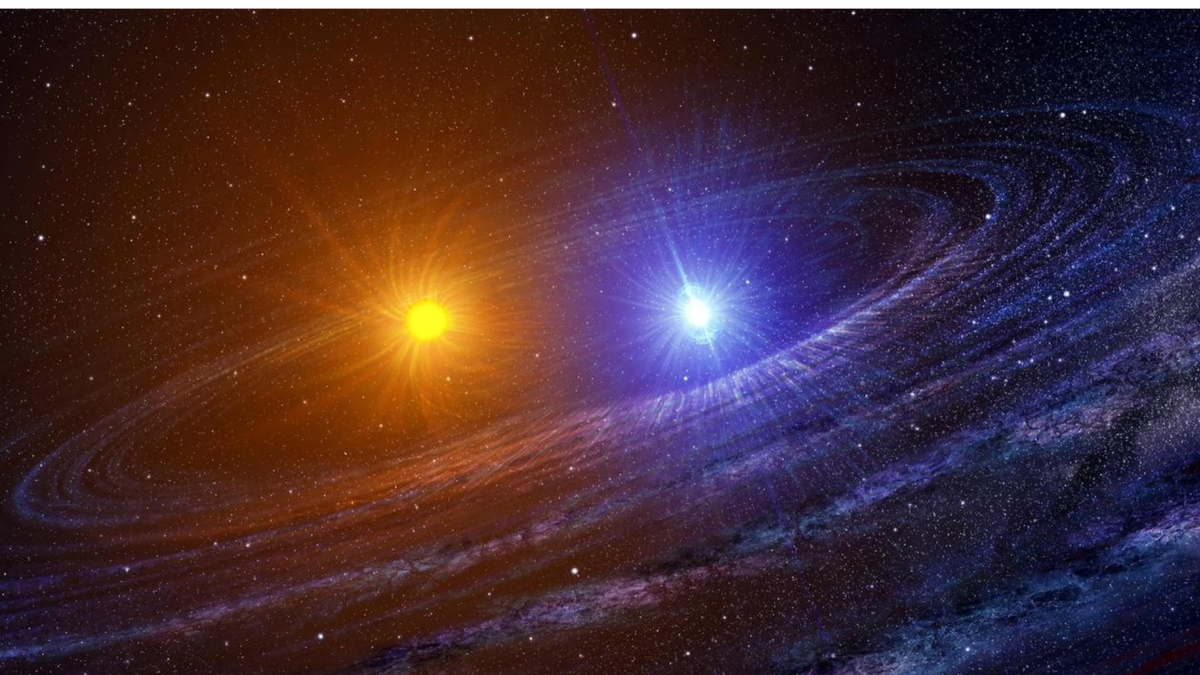

The team, led by researchers at the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands (IAC), has found evidence suggesting that blue supergiants are created when two stars in a binary system spiral together and merge.

Blue giant B-type stars are at least 10,000 times brighter, two to five times hotter, and 16 to 40 times more massive than the Sun. The giant blue supergiants are so extreme that scientists have hypothesized that they may have formed during a rare, brief phase of stellar evolution.

The problem with this idea is that it means that giant blue supergiants are a rare sight, yet they are commonly observed throughout the universe. As a result, its origins have puzzled scientists for decades.

Related: Perhaps 1 in 12 stars has swallowed a planet

There is a clue to the supergiant nature of blue supergiants: they exist alone, without a gravitationally bound companion star. This is strange, because the more massive a star is, the more likely it is to have a companion. About 50% of Sun-sized stars have a companion, but about 75% of more massive stars do.

However, blue giant stars, some of the most massive stars, feel lonely. This may be because blue giant stars exist in systems where their occupants have already spiraled together, collided and merged.

The team of scientists set out to investigate this by analyzing 59 B-type blue supergiants located in the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way, and creating new stellar simulations.

“We simulated mergers of evolving giant stars with their smaller stellar companions over a wide range of parameters, taking into account the interaction and mixing between the two stars during the merger,” said study leader and IAC researcher Athira Menon. He said in a statement. “Newly born stars live as blue giants throughout the second-longest phase of a star's life, when it burns helium in its core.”

The team's findings suggest that blue supergiants are slipping into an evolutionary hiatus in classical stellar physics, a stage of stellar evolution at which astronomers do not expect to see stars. The question is: Can this explain the remarkable properties of blue giant stars? The answer seems to be yes.

“It is striking that we find that stars born from such mergers are more successful at reproducing the surface composition, particularly nitrogen and helium enhancement, for a large portion of the sample than conventional stellar models,” said Danny Lennon, a member of the team and a researcher at the IAC. “This suggests that mergers may be the dominant channel for producing blue supergiants.”

The new results could represent a big step toward resolving a pending problem regarding the birth of giant blue stars, also indicating the importance of binary star mergers in the formation of star clusters and the overall shapes of galaxies.

The next step in this research will see the team shift its attention from the birth of giant blue stars to the death of these massive objects. Scientists will investigate how supernova explosions of giant blue stars create neutron stars and black holes.

The team's research was published earlier this month in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”