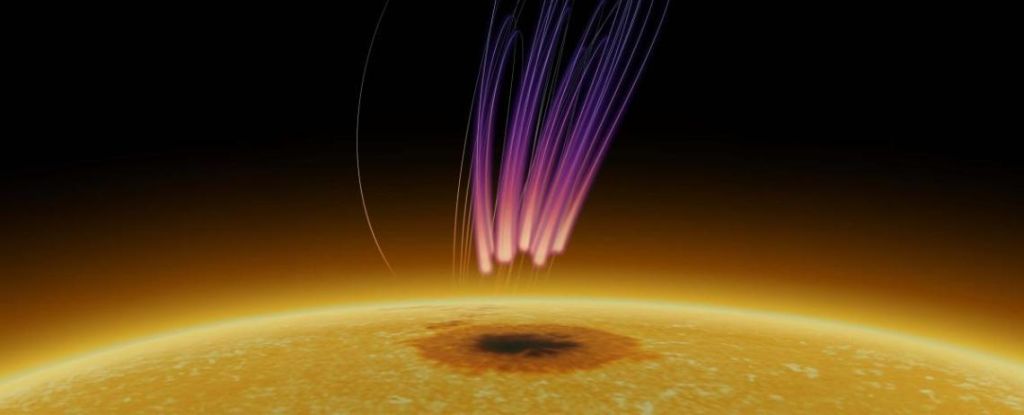

In a startling discovery, scientists have discovered an aurora-like emission in the sun’s atmosphere.

At an altitude of about 40,000 kilometers (25,000 miles) above a thriving sunspot growing in the solar system Photospherea team of astronomers led by Siji Yu of the New Jersey Institute of Technology has recorded an unprecedented type of long-duration radio emission.

The sun emits all kinds of radiation as it does its work, but this, the team says, resembles nothing so much as the aurora borealis.

“We have discovered a strange type of long-period polarized radio bursts emitted by sunspots, which last for more than a week.” Yu says.

“This is very different from typical transient solar radio bursts that typically last minutes or hours. It is an exciting discovery that has the potential to change our understanding of stellar magnetic processes.”

The glowing, wavy aurora borealis are one of the most awe-inspiring sights on Earth, but they are not unique to our home planet, even if their shape varies widely. Auroras have been detected on all the major planets in the solar system, even Jupiter’s four moons.

They form when solar particles become trapped in magnetic field lines, which act as accelerators that increase the energy of the particles before they are deposited, usually in the atmosphere, where they interact with atoms and molecules in it to produce a glow. Here on Earth, we can see that glow dancing across the sky.

But visible light is only part of the aurora’s emission spectrum. there Radio component, also. Although the Sun emits a lot of radio emission through other processes, including bursts of radio activity, the emission swirling above the sunspots was similar in profile to radio auroras.

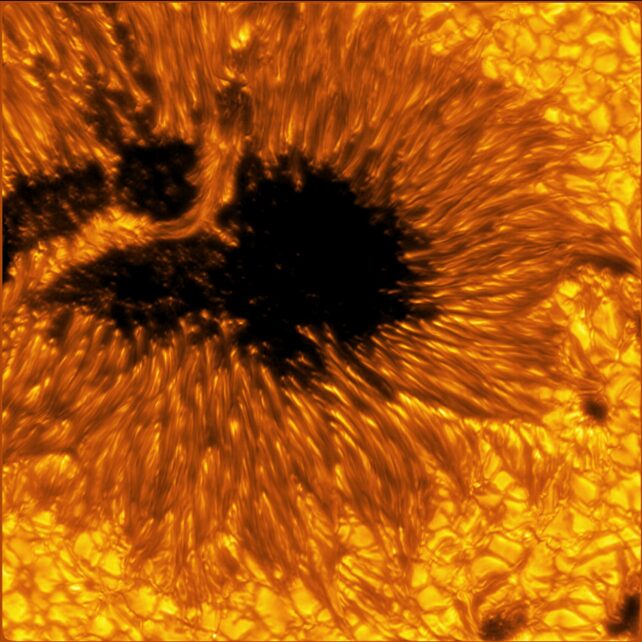

This makes wonderful sense. Sunspots are temporary darker, cooler areas on the surface of the Sun – its photosphere – that are caused by areas of unusually strong magnetic fields that Limitation of solar plasma. No place in the solar system is as full of solar particles as the sun itself.

So it stands to reason that magnetic field acceleration of solar particles could occur there, but much more strongly than on Earth, due to more powerful solar magnetic fields.

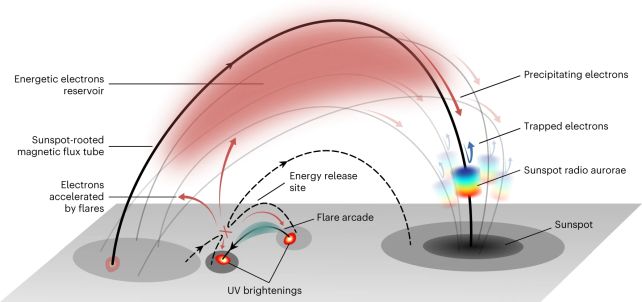

Yo He says The team’s spatial and temporal analysis “suggests this [the emissions] It is due to the emission of an electron cyclotron maser (ECM), which involves energetic electrons trapped within a closely spaced magnetic field geometry.

“The cold, intensely magnetic regions of sunspots provide a favorable environment for ECM emission to occur, drawing parallels with the magnetic polar caps of other planets and stars, and potentially providing a local solar counterpart to study these phenomena,” she says.

In fact, it is not unheard of for a star to emit auroral radio signals. A few years ago, a team of scientists identified a number of stars emitting uncharacteristic radio waves, which they linked to the existence of an exoplanet orbiting a nearby planet whose atmosphere was rushing into the star to generate auroral emission.

The solar system’s planets are too far from the Sun to produce a similar effect, but we are close enough to the Sun to see faint auroral emissions that we might miss in a distant star.

Researchers believe that flare activity in areas not far from sunspots injects energetic electrons into magnetic field loops embedded in sunspots, triggering what researchers call “sunspot radio afterglow.” It’s one of the clearest pieces of evidence yet for the mechanisms involved, suggesting new ways to study stellar magnetic activity and the behavior of stellar spots on distant stars.

The team plans to study archival data to see if they can find evidence of aurorae in past outbursts of solar activity.

“We are beginning to piece together the puzzle of how energetic particles and magnetic fields interact in a system with long-lived stellar spots.” says solar physicist Surajit Mondal from the New Jersey Institute of Technology, “not only on our sun but also on stars outside our solar system.”

The research was published in Nature astronomy.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”