Doubts about the possibility of a lake of liquid water buried beneath Mars’ southern ice sheet have been raised by new computer simulations, which suggest that closely compressed layers of ice could produce the same radar reflectivities that liquid water can.

This is because the surface Mars He is so cold And the Atmosphere The pressure is too low to allow liquid water to stay very close to the surface. However, at the base of the Antarctic ice sheet, temperature and pressure conditions, with the help of a little natural antifreeze, can allow salt lakes to exist.

Related: Water on Mars: Exploration and Evidence

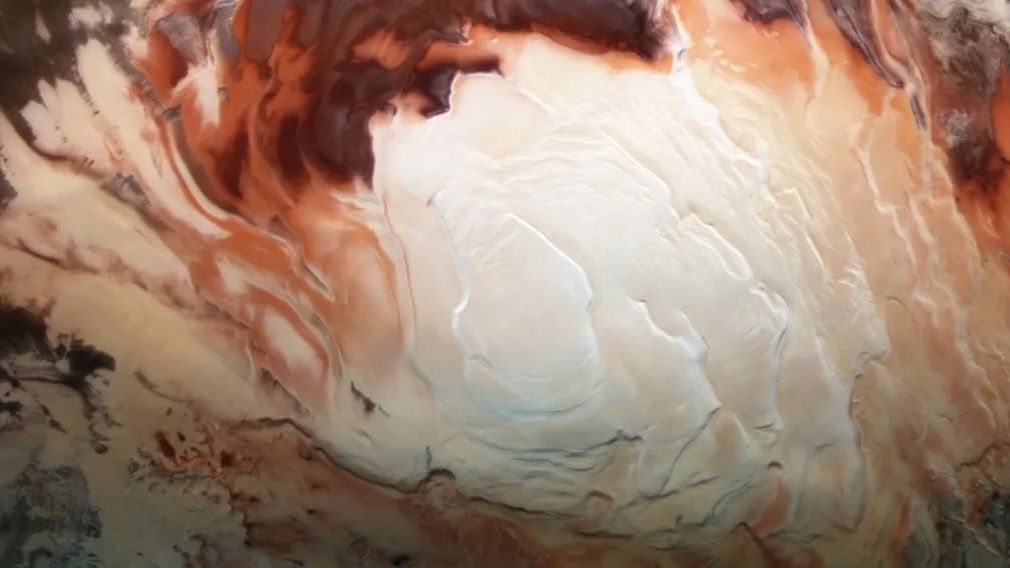

This image taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter shows the ice sheets at Mars’ south pole. (Image source: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona/JHU)

This antifreeze can come in the form of calcium and magnesium perchlorate, a chemical compound found on Mars by NASA. Phoenix mission in 2008. Magnesium and calcium perchlorate, when dissolved in water, will lower their freezing points to at least minus 68 degrees Celsius and minus 75 degrees Celsius (minus 92 degrees Fahrenheit and minus 103 degrees Fahrenheit), respectively — very close to Expected temperature of 68 below zero. °C (-90°F) at the base of the ice sheet. Thus, it is not a stretch to imagine local conditions of temperature, pressure, and perchlorate concentration combining to allow large pools of liquid water on Mars.

Further evidence for the existence of these lakes came from measuring surface ice ripples; Liquid water reduces the amount of friction between the ice sheet and the rocks underneath, allowing the ice sheet to flow faster over the rock layer. This increase in flow rate results in troughs and peaks in the surface ice, which is… Exactly what he looked at At Planum Australia.

Despite all this evidence, many in the planetary science community were skeptical; The presence of liquid water on Mars would be an extraordinary discovery and require extraordinary evidence. Now, a team of scientists from Cornell University has fueled the fires of these doubts with new findings that provide an alternative explanation for radar echoes.

“I can’t say it’s impossible for there to be liquid water out there, but we’re showing that there are much simpler ways to get the same observations without having to scale that far, using mechanisms and materials that we know are already out there.” Daniel Lalich of Cornell said in a… statement

A large body of water can reflect radar back to its source due to how flat the lake is, etc Land Bright radar reflections of the type detected by MARSIS almost certainly mean the presence of liquid water, similar to the pockets of water found beneath Antarctica such as Lake Vostok . However, planetary scientists must be careful not to assume that what applies on Earth applies to other planets, where conditions are not the same.

Lalic’s group ran thousands of simulations to test whether multiple closely compressed layers of ice could mimic the lake’s radar signal. Each simulation varied in the thickness and composition of the ice layers (i.e. how dirty they were). They found that in multiple cases, long-standing tightly packed layers of ice crushed under the weight of the ice sheet can produce radar reflections just as bright as those detected by MARSIS.

The trick is “constructive interference” of radar waves. The spatial resolution on MARSIS is limited, and if the ice layers are too thin, the radar will not be able to distinguish them. Each layer will reflect some of the radar beam, and because the layers are squashed together so tightly, the radar echoes overlap and combine, amplifying their power and making them appear brighter.

“This is the first time we have a hypothesis that explains the entire set of observations beneath the ice sheet without having to provide anything unique or strange,” Lalic said. “This result where we get bright, ubiquitous reflections is exactly what you would expect from thin-layer interferometry in radar.”

For now, the question of whether there is a salt lake beneath the Antarctic cap remains unanswered, but Lalic says the simulations at least provide a much simpler, and, in his view, more likely explanation than the lake.

“The idea of liquid water even being fairly close to the surface was really exciting,” Lalic said. “I just don’t think it’s there.”

Lalic’s team’s findings were published June 7 in the journal Advancement of science