A typical morning in Raberval student town. The bell rings and the students chatter and walk towards their class. In one of these campuses, a debate arises about teaching domestic issues. Located a few kilometers from the Innu community of Mashteuiatsh, this Lac-Saint-Jean secondary school has everything to offer an interesting perspective on the issue.

Indigenous Places met two groups of fourth-year secondary school students to understand their level of knowledge on Indigenous issues.

The first game is scary, the second with a little more excitement. Throughout the discussion, students respond as best they can, in good faith. Together, they were able to identify four First Nations: Innu, Atikamekw, Algonquins (Anishinaabeg) and Greece.

Abenaki

The bell is ringing. Mi’kmaw? Ah, yes, we already talked about that

. Mohawks? No haircuts?

One of the two groups of Marco dello Sparba at the Cité universitaire de Roberval to whom questions were asked.

Photo: Radio-Canada / Jerome Gill-Couture

No one remembers hearing about the Oga crisis in 75 pages of the history of Quebec and Canada. (new window) Talk about it Clash at Oga between the Mohawks and federal and provincial officials

.

Many Atikamekw live in Roberval and attend the student town. However, only about half of the students who took the course had heard about Joyce Echaguan’s death at Joliet Hospital three years earlier. However, they learn that there are many social problems in societies that are dark legacies of colonialism.

Folk cultures and social issues

Valerie Pellerin teaches Ethics and Religious Culture and the New Quebec Culture and Citizenship (CCQ) course at a private school on Montreal’s South Shore. In the interview, he showed no surprise at the Raberwal students’ responses. No doubt his own students would have given similar answers.

In general, the ministry’s program aims at teaching that focuses more on acquiring skills than knowledge. We believe that by allowing the youth to think critically about social inequalities, we allow the youth to gain adequate social awareness regarding tribal issues and other social issues.

Although this approach has obvious advantages, it also has its limitations.

For learning to take root effectively among students, it must be meaningful. Although Aboriginal people are discussed throughout the school curriculum, young people often wonder why we talk about them because we don’t really address their concrete place in today’s society. They find it unnecessary.

Valérie Pellerin has been teaching Ethics and Religious Culture for 6 years. She is currently pursuing a master’s degree whose subject revolves around the decolonization of her teaching position.

Photo: Credit: Valérie Pellerin

Observations verified by Roberwall students. I would like to learn more about the Adigamekwe language and culture. There are many in the school, but while they know a lot about us, I know nothing about them except the harm done to them in the residential schools!

Underlines a student.

We learn how Aboriginal people were in the past, but not now. Today, we always have the impression that things are going to get worse. If we include the history of aboriginal nations in Quebec, we don’t even know a fifth of our history.

Throughout the discussions, a paradox emerges: Students, tired of talking about tribalism, find they don’t know enough.

According to Valérie Pellerin, the lack of proximity to the subject and the appearance of redundancy in the current school system affects not only students but also many teachers.

According to the author, distortion is necessary. One-sided reflection […] A result of our relationship with knowledge

It makes the indigenous people the subject of study. Rather, they should be defined as an integral part of society.

Possible solutions

Quebec Education Minister, Bernard Trinville.

Photo: Radio-Canada / Sylvain Roy Roussel

In a written response to an interview request, Education Minister Bernard Trinville reiterated his commitment to working with his predecessor, Jean-François Roberge. Enhancing relationships with Indigenous communities today and for future generations

.

The Ministry of Education has established a national index of academic success for participating Aboriginal students. This schedule includes a mandate to participate in the development of new subjects and revision of school textbooks.

Project for a new curriculum on culture and Quebec citizenship [implanté progressivement à partir de cette année, NDLR]It is the first to be developed consistently with Indigenous education partners

Mr. Trineville pointed out.

Among these Indigenous partners is the First Nations Education Council (FNEC). For the New Culture and Quebec Citizenship course, we came to clarify some themes,

The director of educational services explains that more expertise is needed CEPN, Annie Grose-Lewis. As regards revision of school textbooks, this is undertaken only occasionally.

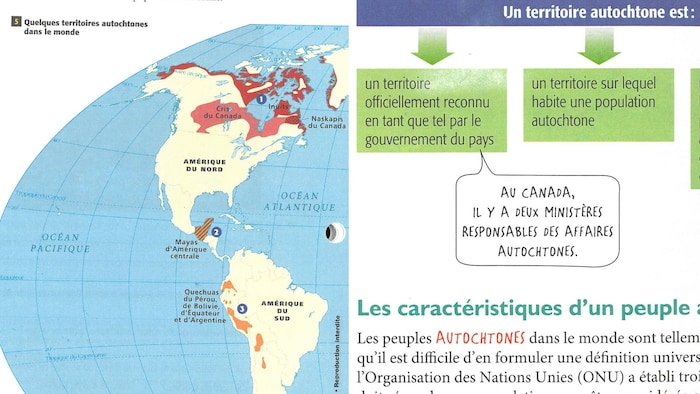

The Ministry of Education’s program manuals always present errors such as the definition of indigenous territory in this Secondary 2 Geography textbook, which is incorrect. A native territory does not have to be recognized by a country’s government. This map suggests that only countries that have signed the modern treaty have territory.

Photo: Radio-Canada / Editions CEC

Plan of new curriculum (new window) Effectively demonstrates a new approach that takes into account the native way of looking at things.

It tells teachers that all classes in Quebec may welcome indigenous students, and that these young people do not want to express themselves in this regard.

The program also recommends bringing a tribe into the classroom.

CCQ and its limitations

According to Valerie Peller, the course represents an interesting step forward, but it cannot alone carry the weight of rapport with Indigenous peoples in education.

CCQ Addresses some Indigenous perspectives, but is not a focused course on them. And we still come back with the issue of teaching young people to think critically about tribal issues without the opportunity to practice concretely.

She explains.

Teachers should also look at how the material will be delivered. Their perspective, the legacy of their education, must be decolonized to address indigenous perspectives.

Refresher courses are offered, but none are mandatory. In fact, a teacher may have learned an ethics program at university [qui existait avant ECR, jusqu’en 2008, NDLR] and is not updated. Imagine the gap

She explains.

If these upgrades are mandatory and unpaid, most teachers will not sign up for them because of the already heavy workload. Not taking this into account shows how limited the government’s real commitment is.

Critical thinking practice

Elders from Mashteuiatsh blocked access to a forest path. (archive photo)

Photo: Radio-Canada

At Roberwall, as the debate unfolded in the ethics class, it was clear that complex questions were being addressed beyond simple common sense.

Most young people were surprised to learn that Quebec’s First Nations rights were not clearly defined for their ancestral territories, except for the Crees and the Naskapi. There is no covenant, laws or success; Only a somewhat abstract recognition since 1982 by Article 35 of the Constitution.

I thought they would say no to a forester or miner who wanted to exploit their territory. It seems to me that this is normal, it is their territory and they have been for thousands of years

, argues a student. This sentiment seems to be shared by the majority class.

The question is very complex. Although they do not have veto rights, First Nations are increasingly asserting their authority over their territories, as demonstrated by the recent withdrawal of a mining company following demands from the Uashat mak Mani Band Council.

The demand for resources – mining, forestry or energy – has not decreased, however, a significant part is located in the ancestral territories of tribal communities. What to do then?

We have to find a way to get along with them, we can’t seize territory or resources while they outlast us. And we must take this into account in our contracts

A student performs an analysis.

Building healthy relationships with tribes means working together while respecting them. This is the compromise

Students agree.

“Music geek. Coffee lover. Devoted food scholar. Web buff. Passionate internet guru.”