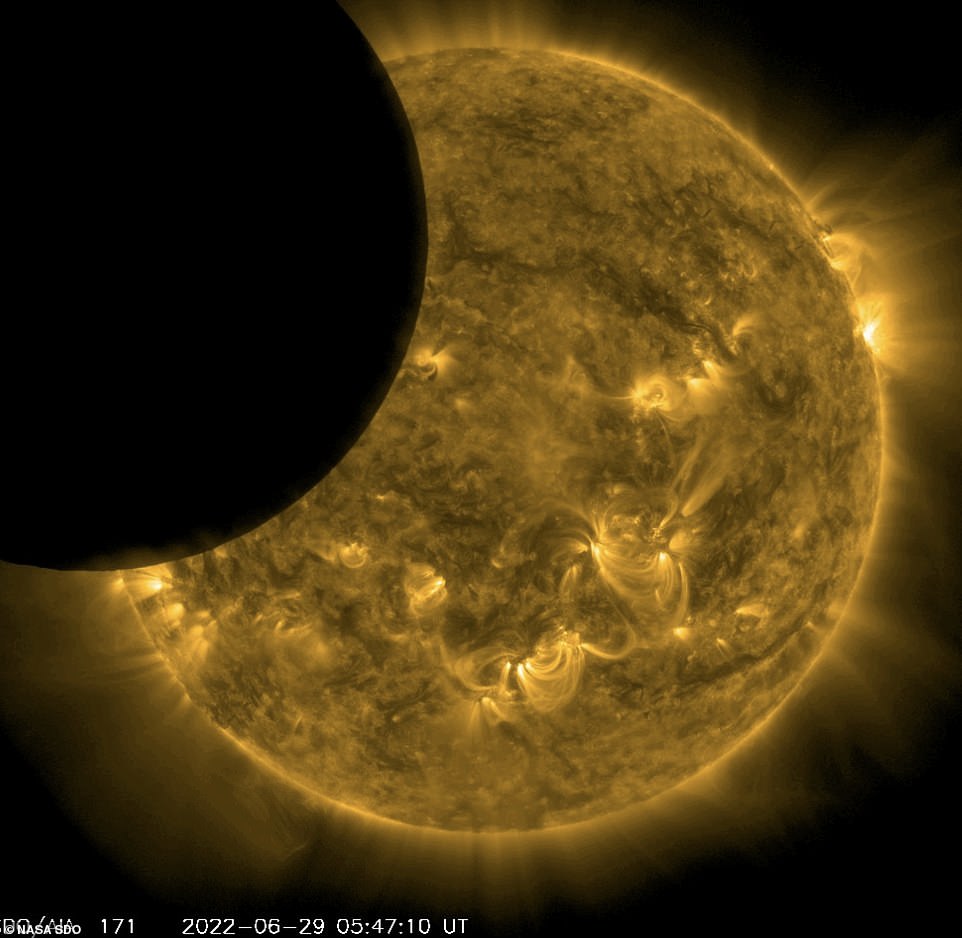

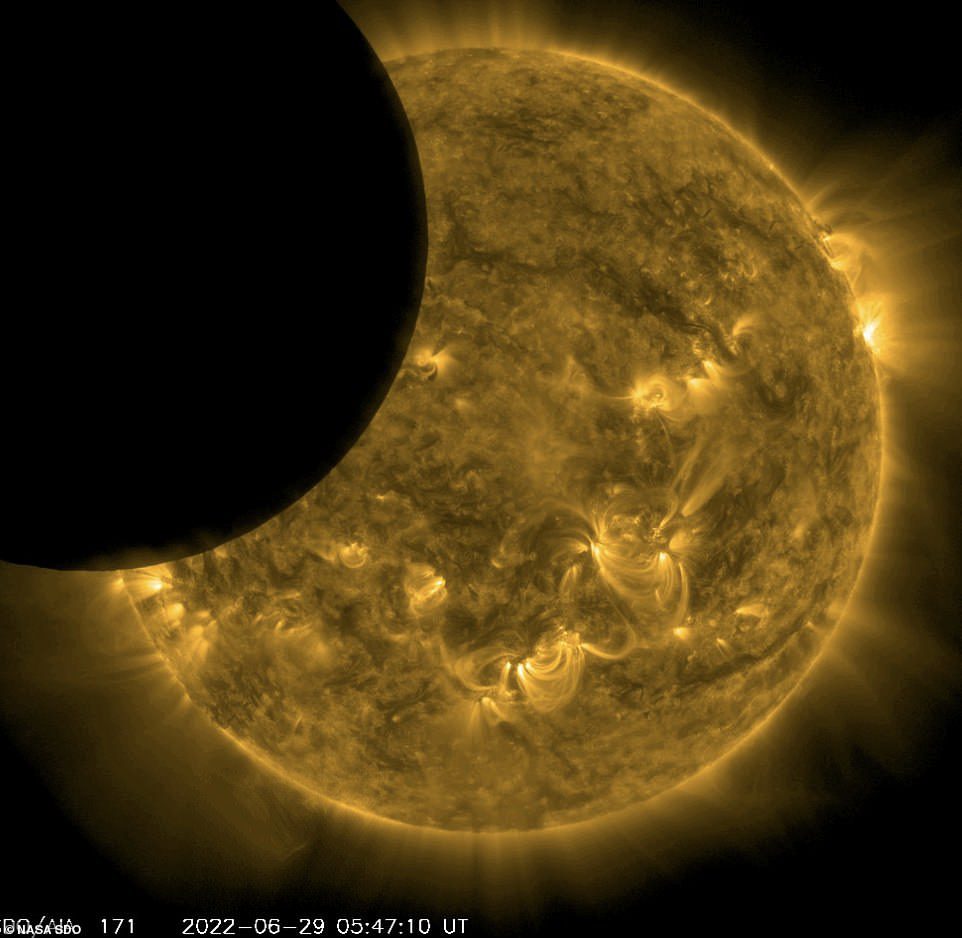

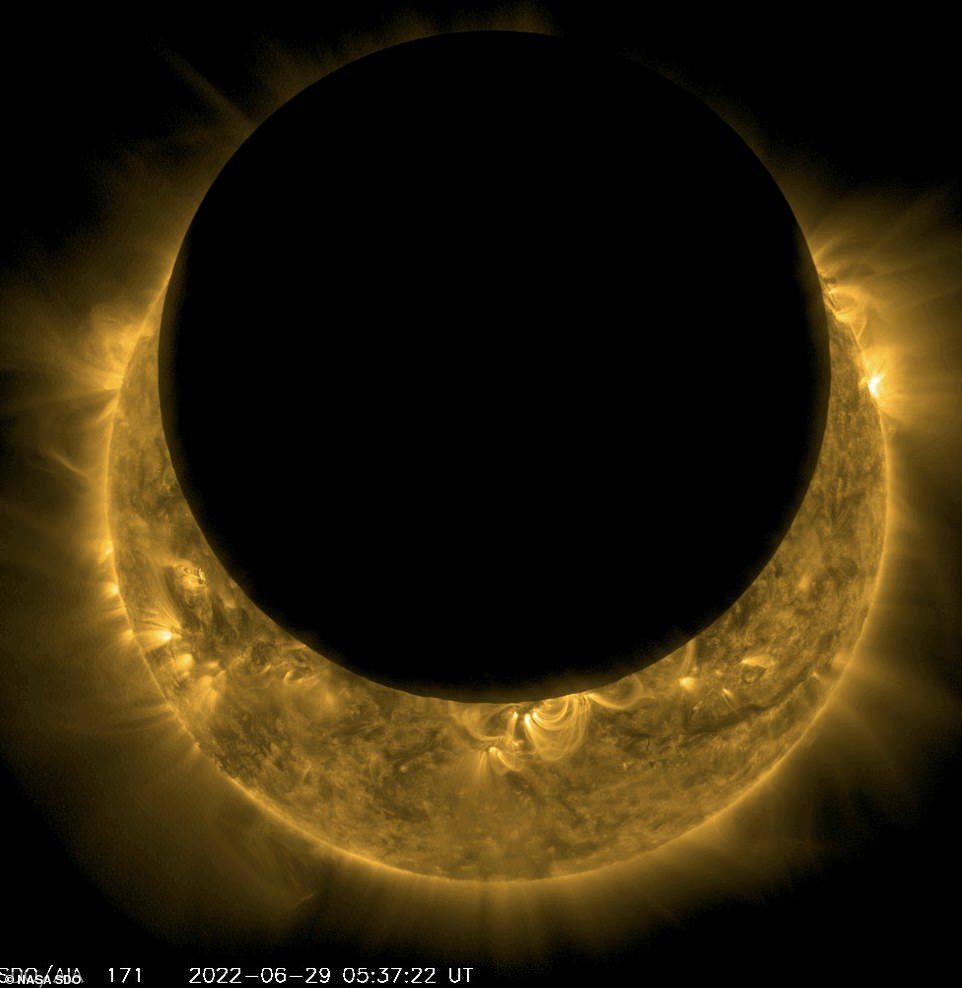

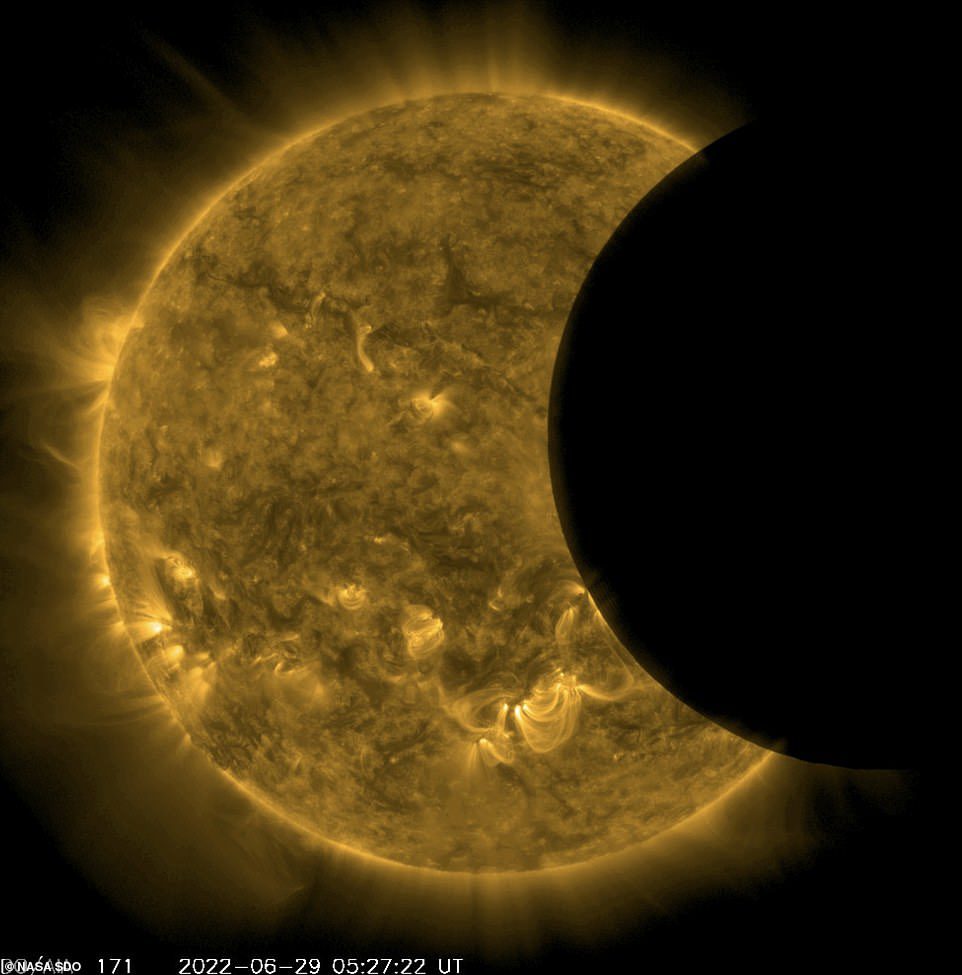

Solar Eclipse… From Space! NASA probe captures moon passing in front of the sun in stunning images capturing ‘lunar mountains lit from the back by the sun’s fire’

- NASA’s spacecraft captured the moon passing in front of the sun from space in a stunning series of photos

- The solar eclipse was not visible from Earth, and it only lasted 35 minutes, but was captured by the camera from space

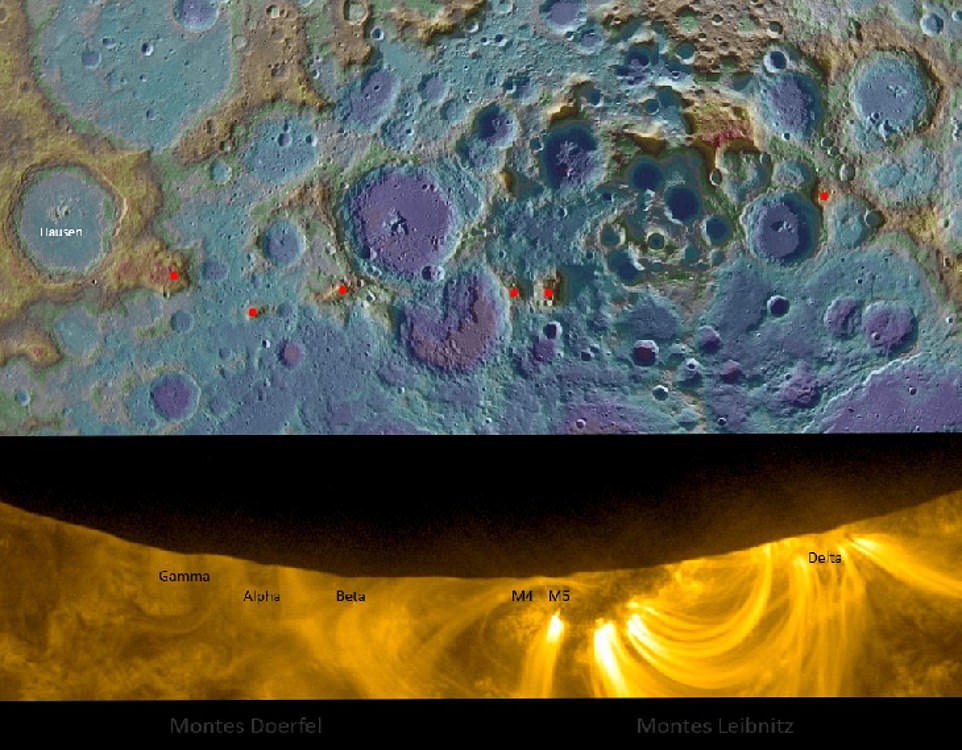

- Close-up images from Solar Dynamics show lunar mountain ranges illuminated from behind by swirling solar flames.

- NASA experts have identified the Leibnitz and Doerfel ranges near the south pole of the moon

Ads

A NASA satellite captured stunning images of a partial solar eclipse from its unique vantage point in space – the only place it was visible.

The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO) imaged the moon passing in front of the sun yesterday from about 5:20 GMT (01:20 ET).

The transit lasted about 35 minutes and at its height the moon covered 67 percent of the fiery surface.

The spacecraft then returned a series of images of the event that showed “the lunar mountains lit from behind by the sun’s fire,” according to experts at SpaceWeather.com.

Outcrops and irregularities can be seen on the surface of the moon it has passed that have been identified as part of the Leibnitz and Doerfel mountain ranges.

NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory captured images of a 35-minute partial solar eclipse from its prime position in space — the only place it was visible.

The Solar Dynamics Observatory photographed the moon passing in front of the sun yesterday from 5:20 GMT (0:20 ET).

The spacecraft brought back a series of images of the event that showed “the lunar mountains lit from behind by the fire of the sun,” according to experts at SpaceWeather.com.

Patricio Leon, of Santiago, Chile, compared close-up images of the moon as it moved across the sun to a topographic map from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter.

He was able to locate the Leibnitz and Doerfel mountain ranges near the lunar south pole during the eclipse.

experts in SpaceWeather.com He said: At the height of the eclipse, the moon covered 67 percent of the sun, and the lunar mountains were lit by the fire of the sun.

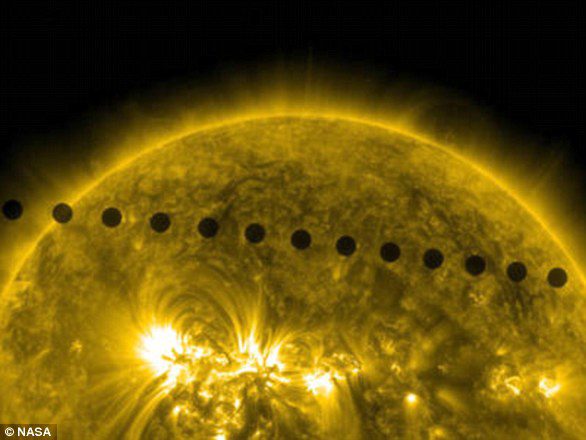

High-resolution images like these could help the SDO science team better understand the telescope.

They reveal how light is reflected around SDO optics and filter support networks.

Once calibrated, it is possible to correct the SDO data for automated effects and refine the images of the sun even more than before.

Launched in 2010, NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory monitors the sun with a fleet of spacecraft, taking pictures of it every 0.75 seconds.

It also studies the Sun’s magnetic field, atmosphere, sunspots, and other aspects that influence activity during the 11-year solar cycle.

The Sun has been experiencing rising activity for a few months now as it appears to be transitioning into a particularly active period of its 11-year activity cycle, which began in 2019 and is expected to peak in 2025.

The sun’s magnetic poles flip at the height of the solar activity cycle, and the solar wind made up of charged particles carries the magnetic field away from the sun’s surface and across the solar system.

This is accompanied by an increase in solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) from the surface of the Sun.

The CME is a significant release of plasma and the accompanying magnetic field from the sun’s corona – the outer part of the sun’s atmosphere – into the solar wind.

Coronal mass ejections affect Earth only when directed in the direction of our planet, and They tend to be much slower than solar flares because they move more matter.

Patricio Leon, of Santiago, Chile, compared close-up images of the moon as it moves across the sun to a topographic map from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. He was able to locate the Leibniz and Doereville mountain ranges near the south pole of the Moon during the eclipse.

The Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), pictured here in the illustration, studies how solar activity is created and how space weather results from that activity.

A The energy from the glow can disrupt the region of the atmosphere through which radio waves are transmitted, potentially causing a temporary interruption of navigation and communications signals.

On the other hand, the CME has the ability to move the Earth’s magnetic fields, creating currents that push the particles down toward the Earth’s poles.

When they interact with oxygen and nitrogen, they help form the aurora borealis, also known as the northern and southern aurora.

Additionally, magnetic changes can affect a variety of human technologies, causing GPS coordinates to stray a few yards and overload power grids when power companies aren’t ready.

There has been no major flare or solar flare in the modern world—the last being the Carrington event in 1859—resulting in a geomagnetic storm with worldwide auroras, as well as fires at telegraph stations.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”