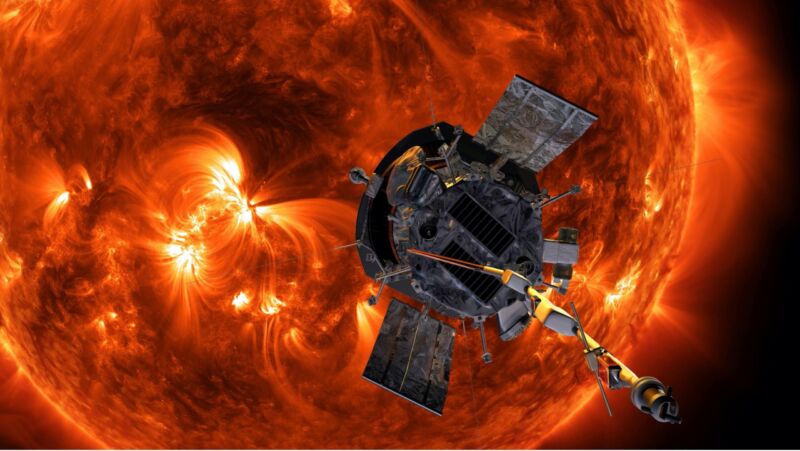

The solar wind streams with charged particles that can light up the aurorae, cause satellites to malfunction, and destroy electrical infrastructure on Earth. Despite their importance, we have a limited understanding of the forces that produce the wind, where it exits from the sun, and what accelerates it toward our planet.

Because the solar wind blows outward with such force, its sheer force has made it nearly impossible for spacecraft to see through the chaos and determine where it was born — until now. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe was able to observe the sun close enough to image the region where the solar wind originates. NASA scientists were previously expected It starts near the surface and then flows through “holes” in the sun’s corona, the outer atmosphere, before being expelled into space. And Parker’s last shot showed they were right.

hole in the areola

Researchers from Parker’s team said: “The fast solar winds that fill the heliosphere originate from regions deep within a magnetic field open to the sun called coronal holes.” Stady Recently published in the journal Nature.

So what are coronal holes? These particularly bright regions in the corona are open regions in the Sun’s magnetic field. Multiple magnetic field lines reaching the surface of the sun pass through each hole, some pointing toward the sun, others away from it. When magnetic domains traveling in opposite directions collide, they break and then connect again in a phenomenon known as magnetic reconnection, releasing plasma that flows along field lines.

This is where Parker Discovery comes in. Parker was able to detect streams of the same high-energy particles in the plasma that pour out from coronal holes. These particles are also found in what is known as the fast solar wind, which is nearly twice as fast as the slow solar wind, and reaches speeds of about 800 kilometers per second (nearly 500 miles/sec). Parker’s Exceptional View can also track the onset of the solar wind from about 8 million kilometers (13 million miles) away. At that distance, the solar wind hasn’t completely transformed into a messy monster yet, so the probe can observe its more orderly beginnings near the surface. The particles of the fast solar wind they glimpsed were so energetic that they were also found to accelerate electromagnetic waves, known as Alfvén waves, which push their particles further.

What drives the solar wind has been a matter of debate for decades, with debate over whether it is driven by magnetic reconnection or Alfvén waves. But until Parker’s advanced instruments could figure out what was going on in the depths of the Sun, there was no way to resolve the controversy.

Find a connection

Parker’s team created a simulation of reconnection that matched the probe’s observations. “Reconnection directly heats the surrounding coronal plasma sufficiently to drive the larger outflow and simultaneously produces the turbulent velocity bursts that ride this outflow,” the researchers said in their study. Stady.

While Parker had tried to pinpoint the origins of the solar wind before, it was misplaced, focusing on a region of the sun’s far side that was too far away to see what was happening in these “coronaviruses”. There was also a chance it wasn’t picking up a lot of activity because it was launched in 2018 during solar minimum (the period of least activity). Solar maximums (the period of greatest impact) occur every 11 years; The next solar maximum will be in 2025, but we didn’t have to wait for the maximum to catch some coronal holes.

Understanding the source of the solar wind should help us predict when it will head our way and how fast it will reach our planet. Knowing how to plan ahead may enable us to protect satellites, electrical grids, and other sensitive equipment. This is especially important as we approach the solar maximum when the ultra-fast solar wind is most likely to hit Earth.

Parker will be able to venture closer to the Sun in the near future. Its instruments can take heat up to 6.4 million kilometers (4 million miles), twice as close as this time around. For now, he continues to stare at the sun.

Nature, 2023. DOI: 10.1038 / s41586-023-05955-3 (about DOIs).

Elizabeth Raine Creature Writes. Her work has appeared on SYFY WIRE, Space.com, Live Science, Grunge, Den of Geek, and Forbidden Futures. When not writing, she either changes shape, draws, or disguises herself as a character no one has ever heard of. Follow her on Twitter: @hravenrayne.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”