Inspired by insects, robotic engineers create machines that can aid in search and rescue, pollinate plants and detect gas leaks

Heavy robots are limited in what they can do. Building smaller, more agile robots, similar to how insects move and work, could greatly expand the capabilities of robots.

“If we think about insect jobs that animals can’t do, it inspires us to think about what smaller robots can do, which larger robots can’t,” said Kevin Chen, assistant professor of electrical engineering at MIT.

Most of the developments are in the research phase, years of marketing. But they offer tempting solutions to a range of industries, including emergency response, agriculture and energy.

Experts said the research is fast-paced for several reasons. Electronic sensors are getting smaller and better, in large part due to smartwatch research. Manufacturing technologies have evolved, making it easier to build small parts. Small battery technology is also improving.

But there are still many challenges. Small robots cannot copy the workload of a larger robot. Although the batteries are improved, they need to be smaller and more powerful. The miniature parts that convert energy into automated motion, called actuators, must become more efficient. Sensors should be lighter.

“We start by looking at how insects solve these problems, and we’re making significant progress,” said Sawyer B. Fuller, an assistant professor who directs the University of Washington’s Autonomous Insect Robotics Laboratory. “But there are a lot of things… we don’t have yet.”

Much of the insect robotics research can be broken down into a few areas, the researchers said. Some scientists are building an entire robot to mimic the movement and size of real insects, such as bees and lightning bugs. Others put electronics on and control living insects, essentially creating cyborgs (beings with both organic and mechanical aspects). While some are experimenting with a hybrid – connecting parts of a live insect, such as antennae, to a robot.

Robotic engineers began searching for insects for inspiration about 10 to 15 years ago. At that time, only a few research laboratories were studying it. “Ten years ago, I honestly think it sounded more like science fiction,” Chen said.

But over the years, more researchers have entered the space, in large part due to advances in technology. Chen added that much of the activity has been driven by developments in carbon fibers and lasers, which can make “very cool features and complex structures” on a small scale.

Electronic sensors have also improved, in large part because smartphones and smartwatches spurred research to make smaller electronic parts.

“If you think about your smartphone, there are many sensors inside,” Chen said. “You can really take advantage of a lot of these sensors or put those sensors into small scale robots.”

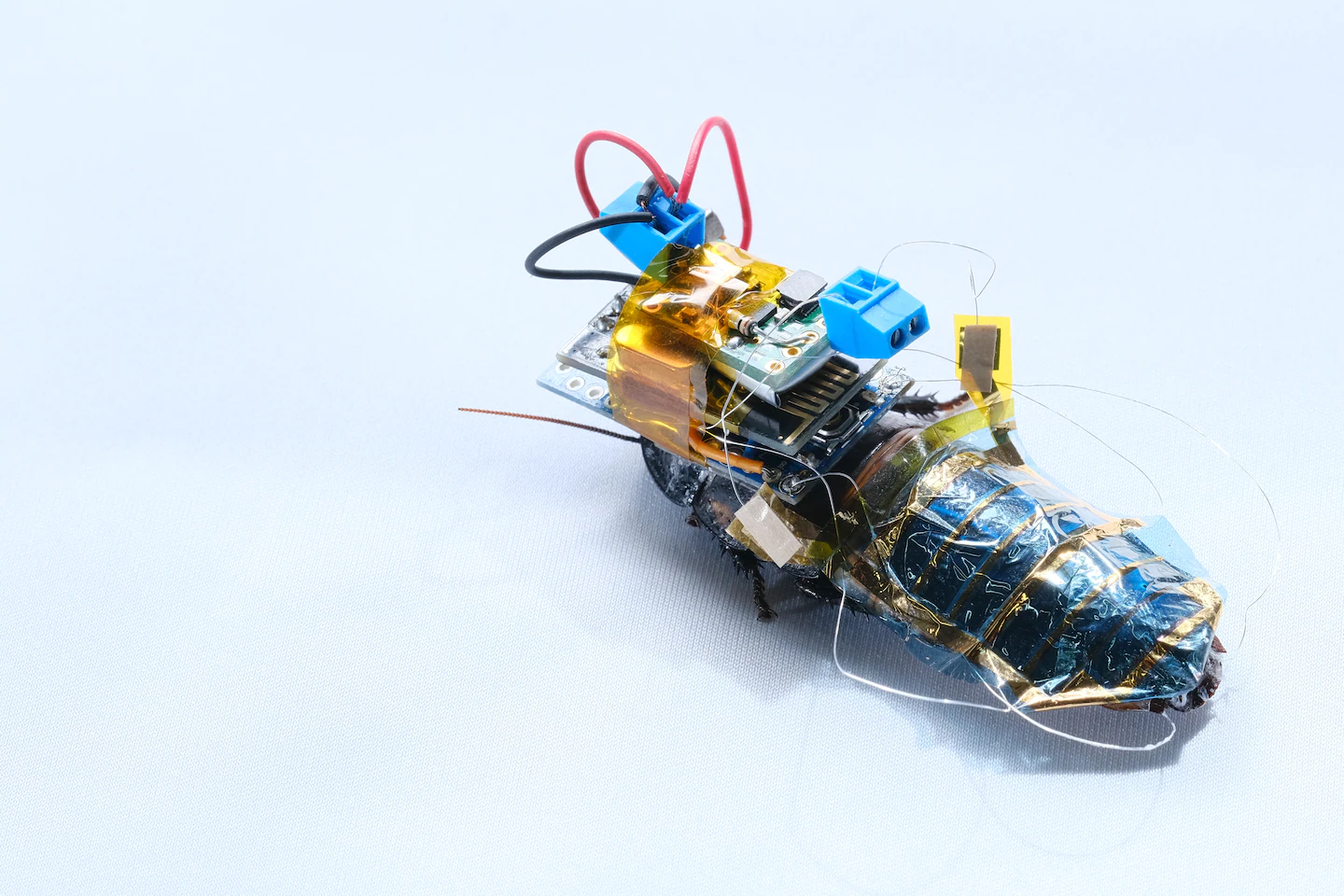

Kenjiro Fukuda, a researcher at the Riken Institute for Thin Devices in Japan, leads a team attaching 3D-printed sensors to hissing Madagascar crickets. The sensors act like a small backpack containing solar panels for power; A blue-toothed sensor for remote control and specialized computers connects to the cockroach’s abdomen and sends small shocks to direct it to the left or right.

Fukuda envisions these cyborg cockroaches helping out in emergencies, such as an earthquake. He said survivors may be under the rubble and difficult to see with the naked eye.

Cockroaches can be controlled remotely, releasing them into the rubble using carbon dioxide sensors and cameras on their backs, helping to find people in need of rescue.

“Big people can’t get into the rubble,” Fukuda said. “Little bugs or little robots can do that.”

Fukuda said he could also apply this approach to other insects with large shells, such as beetles and cicadas. But several improvements need to be made to the battery design and the amount of power the parts draw before this solution can be deployed in real life, he said.

When it comes to cyborgs, not everyone is excited. Jeff Sebo, professor of animal bioethics at New York University, said he’s concerned that live insects feel controlled by humans while they’re carrying heavy technology. He said it’s unclear whether they feel pain or distress because of it, but that doesn’t mean humans should ignore it.

“We don’t even pay lip service to their welfare or their rights,” he said. “We don’t even go through with suggesting that there are laws, policies, or review boards in place so that we can try and relentlessly try to minimize the harm we’re imposing on them.”

Chen makes flying robots from lightning bugs. These are fully automated machines that mimic the way insects move, communicate and fly.

Inspired by the way lightning bugs use electroluminescence to glow and communicate in real life, Chen’s team built soft artificial flight muscles that control the robot’s wings and emit colorful light as it flies.

This could enable a swarm of these robots to communicate with each other, and could be used to pollinate crops on vertical farms or even in space, Chen said.

“If I wanted to grow crops in space, [I want] Pollination,” he said. “In this scenario, a flying robot would be much more convenient than sending out bees.”

Fuller said he looks at bugs when he makes little robots because it’s so much better than relying on his imagination. “You see insects doing crazy things that you wouldn’t be able to do on a human level,” he said. “We’re just looking at how insects do that.”

Fuller’s team is working on building a robotic fly. Similar to cyborg cockroaches, flies can be used for search and rescue missions. They can also be unleashed to fly and look for chemical leaks in the air or cracks in the pipeline infrastructure.

“You open a bag and these little robot flies fly around,” he said. “Then, once you know where the leak is, you can correct it.”

Fuller said he acknowledges there is a long way to go before his bots can do it. It would be difficult to miniaturize all the sensors, power packs, and parts needed for robots to transmit data and send it back to teams. Making batteries small enough but powerful enough to power robotic jobs is a daunting challenge. Stable robots that can flap their wings but also carry sensors require more design research.

Despite the difficultiesAnd the Scientists are also working on taking parts of a live insect, such as a moth’s antennae, and attaching them to a robot that could one day read data from it, he said. He said this hybrid method could be a great place for researchers in insect robotics.

“I think that’s the way we should go,” Fuller added. “Take the pieces of biology that are already working well and do the rest automated.”

“Web specialist. Lifelong zombie maven. Coffee ninja. Hipster-friendly analyst.”