NASA is not asking SpaceX to prove that its spacecraft’s human landing system can lift off from the lunar surface before it is used on the Artemis III mission, and the experimental craft will serve as a “skeleton” for the actual lander. NASA chose SpaceX to build the Artemis III probe, and an uncrewed test flight preceded it, but the head of NASA’s HLS program said today that the offer does not include a liftoff. She also stressed that the Starship is still in the design and development phase with many challenges ahead, and is not ready to go as some believe.

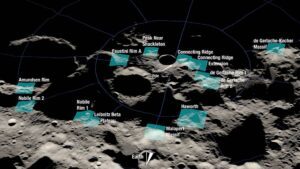

Lisa Watson Morgan, HLS program manager at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, spoke to NASA’s Lunar Exploration Analysis Group this morning with other NASA officials about the recent selection of 13 areas in the lunar south pole for the Artemis III landing.

Artemis III will return humans to the lunar surface for the first time since the Apollo program. NASA currently expects to land in late 2025, just over three years from now.

SpaceX has been developing the Starship for several years. Five test flights of Phase II prototypes took place at an altitude of about 10 km between December 2020 and May 2021. The first four fires are over, But the fifth succeeded. The much larger first stage was not carried out despite “appropriate checks” of the fully assembled vehicle at SpaceX’s Boca Chica, Texas test facility.

SpaceX founder and chief engineer Elon Musk tweeted yesterday that launching the Starship into orbit is one of his main goals this year.

SpaceX plans to use the Starship for many purposes – launching satellites into Earth orbit as well as launching people and goods to the moon and Mars. The Starship name is used for the entire vehicle and for the second stage only.

It is the second stage that will go to the moon.

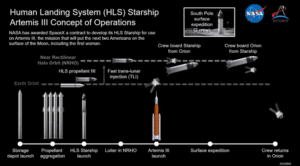

The spacecraft is not designed to fly directly to the moon like NASA’s Space Launch System. Instead, the first stage only puts it in Earth’s orbit. To move forward, it must be filled with fuel at a fuel depot that has not yet been built. Other ships are needed to deliver fuel to the depot.

Watson-Morgan described the concept of operations for Starship’s Artemis III mission, starting with launching the fuel depot, then launching a number of “fuel pools” to fill the depot, and then launching the spacecraft that will go to the moon.

Its slide shows four firings to collect the propellant, but that’s not a consistent number. “How many? Although a lot is needed, this is how many will be released.”

SpaceX and NASA are working together to demonstrate cryogenic fluid management in orbit and “we still have a lot of challenges to overcome.”

“You can… you might feel that [SpaceX’s] The system is ready to operate. It hasn’t happened yet. We are into design and development. …we are still developing. We are still changing. And we’ll get smarter and then we’ll have an amazing launch and we’ll have an amazing landing.” Lisa Watson Morgan

The landing of two NASA astronauts on the Artemis III will be preceded by an uncrewed test planned for 2024, but she made it clear that NASA is only asking SpaceX to prove a safe landing. not take off.

“The unmanned demo doesn’t have to be the same spacecraft you see for the test crew. It’s going to be a skeleton because it just has to land. It doesn’t have to go back down, just for clarity. We obviously want it to do that, but the requirements for it are that landing”. Lisa Watson Morgan

The discussion took place in the context of the scientific investigations that could be conducted on the Artemis III mission. Working with SpaceX and a select group of scientists, NASA has selected 13 regions in the moon’s south pole where the landing could occur. NASA is now seeking input from the broader lunar science community to narrow the list.

Many factors come into play, especially lighting conditions, which are very different from the six Apollo landing sites that were closer to the equator. Antarctica is of great scientific interest and its permanently shaded areas are believed to contain water ice that could be used to support human outposts and other purposes.

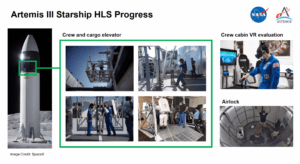

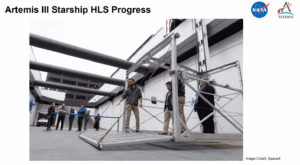

One scientist from the audience expressed concern about whether the crew would actually be able to go down to the surface and back to do science. The spacecraft is very tall and has an elevator for going up and down.

Watson Morgan gave assurances that she would succeed. She said the elevator is tolerant of multiple errors, and NASA and SpaceX are working together in tandem to test it, including with crews.

Logan Kennedy, HLS Surface Lead at Marshall, showed two slides of progress. He said the second slide shows what it will look like when people next set foot on the moon.

He also expressed confidence in the elevator. One concern is lunar dust, which sticks to everything and can spoil the mechanisms. He insisted that the elevator is designed to operate in that environment, with a lot of reservation in the models because not much is known about lunar soil – regolith – at the south pole from the Apollo sites.

Last update: August 23, 2022, 4:26 PM ET

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”