The stone tool was cemented into a handle made of liquid bitumen with the addition of 55 percent ochre. It is no longer sticky and can be easily handled. Credit: Patrick Schmidt

Analysis of 40,000-year-old tools revealed a surprisingly sophisticated level of construction.

A team of researchers has discovered that Neanderthals made stone tools using advanced multi-component glue. This discovery, the oldest known example of such an advanced adhesive in Europe, suggests that these early human relatives possessed a greater degree of intellectual and cultural sophistication than previously thought.

Work, reported in the magazine Advancement of scienceThis included researchers from New York University, the University of Tübingen, and the National Museums in Berlin.

Technical innovations by Neanderthals

“These surprisingly well-preserved tools display a technical solution very similar to examples of tools made by early modern humans in Africa, but the exact recipe reflects Neanderthal 'spin', the production of handles for portable tools,” says Radu Iovita. , Associate Professor at New york universityCenter for the Study of Human Origins.

The research team, led by Patrick Schmidt from the Department of Early Prehistoric and Quaternary Ecology at the University of Tübingen, and Ewa Dutkiewicz from the Museum of Prehistory and Early History at the National Museums in Berlin, re-examined previous finds from the archaeological site of Le Mostier in Berlin. France, which was discovered in the early twentieth century.

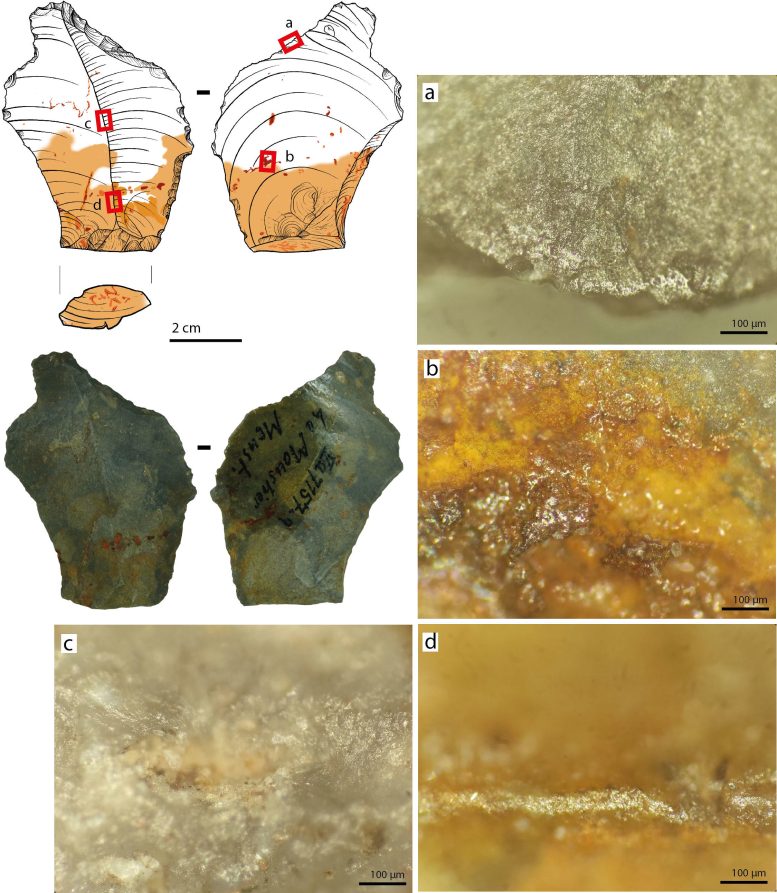

Micrograph showing traces of wear on a tool used by Neanderthals during the Middle Paleolithic. The locations of the micrographs on the artifact are indicated in the drawing (top left) in red. A) Polishing or gloss on the active edge of the tool handle. b) Polish the colored spots within the area covered with adhesive. c) The ridge between concave surfaces formed by the removal of stone pieces that have been removed, rather than naturally worn away. d) Faded or frayed edge in the grippable area covered with adhesive. Comparison between (c) and (d) indicates that the worn part is within the area covered by the designed adhesive grip. Images are shown in microns. Image source: Drawing by Dr. Greenert, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

The stone tools from Le Moustier – used by Neanderthals during the Middle Paleolithic of the Mousterian period between 120,000 and 40,000 years ago – are preserved in the collection of the Berlin Museum of Prehistory and Early History and have never been examined in detail before. The tools were rediscovered during the group's internal review and their scientific value was recognized.

“The items have been individually wrapped and haven't been touched since the 1960s,” says Dutkiewicz. “As a result, the adhering remains of organic matter are very well preserved.”

Uncovering old technologies

Researchers discovered traces of the ocher and bitumen mixture on many stone tools, such as scrapers, flakes and blades. Ocher is a natural earth pigment. Bitumen is a component of asphalt and can be produced from crude oil, but it occurs naturally in soil.

“We were surprised that it was more than 50 percent ocher,” Schmidt says. “This is because air-dried bitumen can be used as an adhesive without change, but it loses its adhesive properties when such large proportions of ochre are added.”

He and his team examined these materials in tensile tests, used to determine strength, and other metrics.

Liquid bitumen and earthy ocher before mixing. Credit: Patrick Schmidt

“It was different when we used liquid bitumen, which is not really suitable for adhesion. If 55% ocher is added, a malleable mass is formed,” says Schmidt.

The mixture was sticky enough for the stone tool to remain stuck to it, but not to stick to the hands, making it a suitable material for the handle.

The importance of the results

In fact, microscopic examination of traces of wear on these stone tools revealed that the adhesives found on the tools from Le Mustier were used in this way.

“The tools showed two types of microscopic wear: the first is the typical polishing on sharp edges that is usually caused by the action of other materials,” explains Iovita, who conducted this analysis. “The other is a shiny coating distributed throughout the supposedly hand-held portion, but nowhere else, which we interpret to be the results of wear from the ocher due to the movement of the tool within the handle.”

Implications for human evolution

The use of multi-component adhesives, including various sticky substances such as tree resins and ochre, was previously known from early modern humans. Homo sapiens, in Africa but not from early Neanderthals in Europe. Overall, the development and use of adhesives in tool making is considered some of the best physical evidence of the cultural evolution and cognitive abilities of early humans.

“Combined adhesives are among the first expressions of modern cognitive processes that are still active today,” says Schmidt.

The authors point out that in the Le Moustiers region, ocher and bitumen had to be collected from remote sites, requiring a great deal of effort, planning and a targeted approach.

“Taking into account the general context of the finds, we assume that this adhesive was made by Neanderthals,” Dutkiewicz concludes.

“What our study shows is that early Homo sapiens in Africa and Neanderthals in Europe had similar thinking patterns,” Schmidt adds. “Their adhesive techniques are equally important to our understanding of human evolution.”

Reference: “Ocher-based composite adhesives at Mousterian writing site document complex knowledge and high investment” by Patrik Schmidt, Radu Iovita, Armel Shari Duhaut, Günter Müller, Abai Namin, and Ewa Dutkiewicz, 21 February 2024, Advancement of science.

doi: 10.1126/sciadv.adl0822

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”