Space is very hot right now. Uncrewed Artemis I mission On its way to lunar orbit, it is the first in a series of missions that plan to return humans to the moon by the end of the decade. spacewalk in The International Space Station went down this week, and it has been They streamed live. they were Shit swings at asteroids To prove our ability. And our new friend, the James Webb Space Telescope, is doing its thing, quietly overhauling our entire understanding of how the universe works.

The JWST floats a million miles from Earth and sends back images that make Hubble look like a real piece of shit. Understandably, the photos of Webb that get the headlines are The ones that are mind blowing—Pictures that are particularly beautiful or gorgeous that inspire awe. Web still takes a lot of those. But those artistic images are, in a sense, the PR telescope to justify their existence to the wider public. The actual science happens in the analysis of less exciting data: things that aren’t even in the visible spectrum, or in the close analysis of relatively unspectacular images. Yesterday’s big news comes from these action photos.

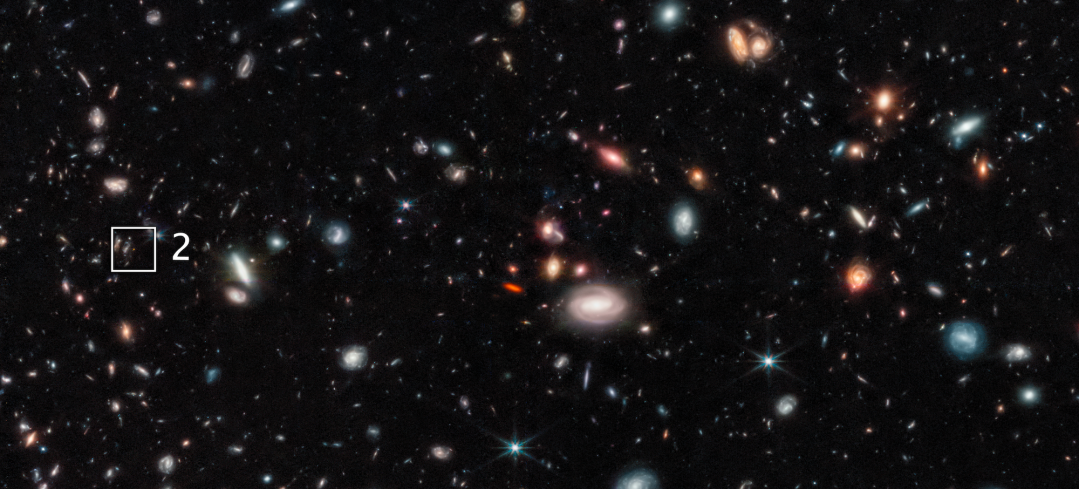

I realize I’m running the risk of underselling this, so: naturally These photos are amazing, even if they aren’t pillars of creation. And what they show – that is, what is blown up in Figure 2 in the lower center – is an absolute formula that melts into the brain. It’s the galaxy GLASS-z12, and it’s believed to be 13.45 billion years old, or just 350 million years after the universe came into being in the Big Bang. It is the farthest starlight we have ever seen.

But it wasn’t just the existence of a galaxy that got scientists excited — we already knew there would be galaxies from around that time, and we knew JWST’s superior imaging would reveal them. What was unexpected was how easy it was to find.

“Based on all the predictions, we thought we had to search a much larger area to find such galaxies,” Marco Castellano said from the National Institute of Astrophysics in Rome, who led One From two Research papers published thursday in Astrophysical Journal Letters. Scientists had a model, based on current understanding, of how many of these bright, fully formed galaxies in the early days of the universe would be present there. This model predicted that a piece of the sky about 10 times larger than what Webb captured would be needed to find it. Instead, scan the Web quickly two These galaxies, discovered by scientists within a few days after the publication of the data for the study.

What this means is that our models were wrong, and that bright, densely populated galaxies may have formed faster and more frequently after the end of the stellar Dark Ages–about 100 million years after the Big Bang, when conditions in the early universe finally allowed gravity to begin building up stars–than we had imagined.

We were wrong! That’s so cute! You know we were wrong, like, the whole literal point of science! Knowing that our models and predictions were inaccurate allows us to make new models to better explain the observations, bringing us closer to being right. Science iterative, and these small discoveries, rather than big, sparkling pictures, are how the JWST will help us write and rewrite the early history of our universe.

“These notes make your head explode.” Paola Santini said, co-author of Castellano et al. paper. “This is a whole new chapter in astronomy. It’s like an archaeological dig, and all of a sudden you find a lost city or something you didn’t know about. It’s amazing.”

These two new galaxies make some interesting observations. And it is Much brighter than we expected, and brighter than anything else closer to Earth. “Its extreme brightness is a real puzzle,” said Pascal Ochs, a co-author of the second paper published today. But there is an attractive possibility. It is assumed that at the beginning of the Universe, stars consisted only of hydrogen and helium, simply because they had not yet had time to produce heavier elements by means of nuclear fusion. Those so-called Population 3 stars would be incredibly hot and incredibly bright, and although it’s been a long time theory, it’s never been noticed. Maybe yet.

This is, quite literally, hot shit. Thanks Web.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”