New York prosecutors this week returned two modernist drawings seized by the Nazis more than 80 years ago to relatives of a Jewish cabaret artist murdered in Dachau.

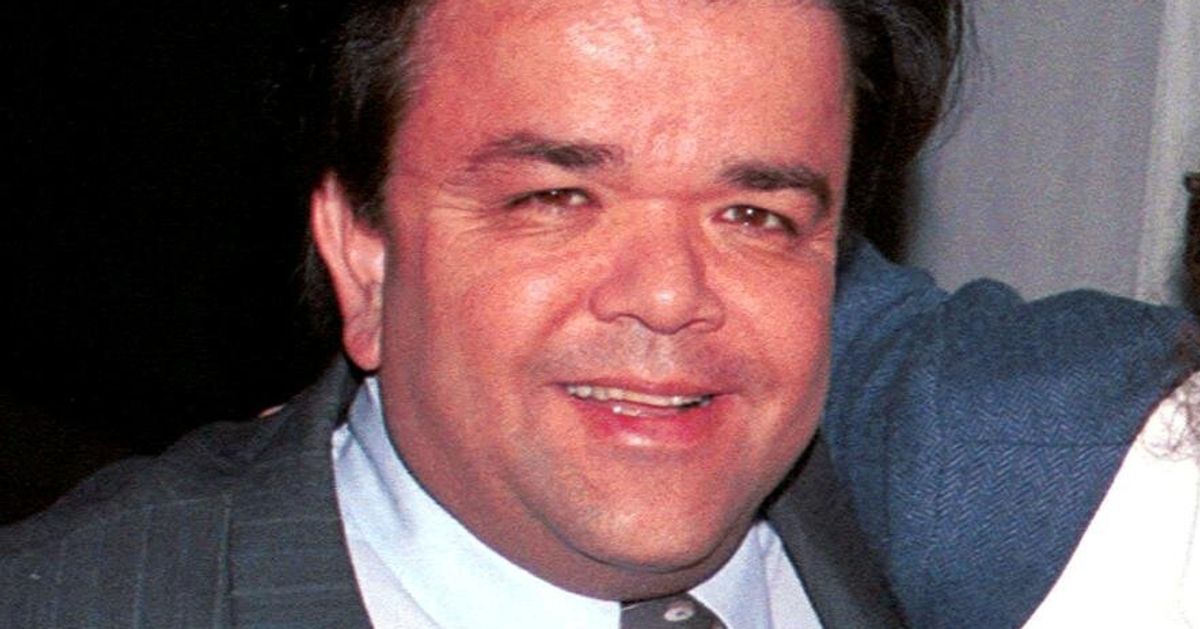

Fritz Grünbaum, the Viennese singer and comedian who was outspoken against Hitler, is believed to have owned at least 450 works of art before the Nazis annexed Austria. About a dozen were recovered by his relatives.

In some cases when the Nazis arrested Jews and sent them to concentration camps, officers removed family possessions, including priceless works of art. Nazi officials placed the stolen artworks in their galleries and homes and hid them in caves and salt mines. Allied “Monuments Men” worked to recover many artifacts following World War II. As art resurfaced across Europe, the original owners of the work were often not revealed during sales, making it difficult for descendants of people killed in the Holocaust to recover their family's stolen property.

Many families, like the Grunebaums, spent decades tracking down and trying to prove they owned valuables stolen by the Nazis.

After years of searching, relatives finally regained ownership of two of Grünbaum's drawings by Egon Schiele. Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg announced that objects held by two American art museums had been returned to Grunebaum's descendants. Prosecutors have valued Shelley's 1911 drawing, “Girl with Black Hair,” which was owned by the Allen Museum of Art at Oberlin College in Ohio, at $1.5 million. The second piece, “Portrait of a Man” from 1917, was owned by the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, and its value was estimated at one million dollars. Seven additional works recovered by the DA in New York last fall were valued at $9.5 million.

Detailed records from Nazi officials and art dealers provide clues for Grünbaum family members and prosecutors to track down the long-stolen pieces. Hundreds of paintings and drawings seized from Grünbaum's wife after he was sent to Dachau were found to be scattered in collections across the United States and Europe.

After years of research, every recovery is important.

A relative of the collector, US Judge Timothy Reeve, said in a statement: “This is a victory for justice, and a memorial to a brave artist, art collector and opponent of fascism.” “As the heirs of Fritz Grünebaum, we are grateful that this man who fought for what was right in his time continues to make the world more just decades after his tragic death.”

The bloodiest conflict: When did World War II start? The deadliest international conflict explained.

The Grunebaums auctioned off the pieces they recovered at Christie's and used the proceeds for a fund that provides scholarships to high school musicians from underrepresented communities, Raymond Dodd, an attorney for the Grunebaum family, told USA TODAY. The two Shelley items found on Friday are scheduled to be auctioned in May.

The family also has an active lawsuit to reclaim dozens of objects belonging to Grünbaum that are housed in Austrian museums, Dodd said.

They have clues as to the whereabouts of the other pieces, but Dodd said: “There's a lot of detective work we need to engage in.”

Dodd said the family is grateful to prosecutors like Bragg and Morgenthau who do not want to “turn a blind eye to this terrible crime.”

Seizure of works of art and murder by the Nazis

Grünbaum, who was born in 1880, collected hundreds of works during his decades as an actor in Austria and Germany. He became an outspoken critic of the Nazis One site It is described as a “political cabaret” in Vienna.

“He insisted on showing pieces that openly mocked Hitler, the lack of freedom under Nazism, and the impossibility of dissent in Austria,” according to a history of Music and the Holocaust By ORT, a UK-based charity.

Stepping onto a darkened stage for his final public performance in March 1938, he told the audience he had seen nothing.

Ice skating and Kit Kat rinks: After the Tree of Life shooting, Pittsburgh forged interfaith connections

“I must have wandered into National Socialist culture,” he joked, using another name for Nazis.

Austrian officials subsequently banned him from performing, and days later, the Gestapo arrested him, according to court files.

He was imprisoned in Dachau and performed for other Jews imprisoned there. He remained in the camp until his death on January 14, 1941.

In July 1938, while in Dachau, the Nazis forced him to give his wife Elisabeth power of attorney, forcing her to hand over his entire art collection to the government. Jews were not allowed to own property, and by 1939, the Jewish Property Declaration showed that the Nazis had seized all of his wife's property.

On October 5, 1942, Elisabeth was deported to the Maly Trostinets death camp in Minsk where she was murdered.

Stolen art is resurfacing in Switzerland and Manhattan

Elisabeth's estate declaration includes details of Grünbaum's estate. However, the bulk of the family's artwork disappeared from records after World War II. Allied officials warned that looted Nazi artwork was turning up in American and European galleries and museums.

Documents from 1930 show that the Austrian-Jewish art dealer Otto Kaler knew that Grünbaum owned pieces by Schiele. After the war, Caller bought 20 works.

The pieces ended up at Galerie Saint-Etienne in New York, a modern downtown gallery founded by Callier. The works were later sold to museums and collectors, according to court filings. Heirs will search for these pieces for years.

It wasn't until 1998 that the family had its first breakthrough. Robert Morgenthau, the Manhattan district attorney at the time, seized Schiele's “Dead City 3” from the New York Museum of Modern Art, about four blocks from the Kahler Gallery.

This was the first of twenty works returned to Grünbaum's heirs.

The heirs filed lawsuits against several institutions to reclaim other works of art purchased by Callier after the war. They were hampered by questions about the provenance of the art and documents that showed the works had been properly acquired by other institutions. The Grünbaum family and art historians dispute this evidence.

The family waited for a breakthrough until September 2023, when the Manhattan District Attorney's Office and investigators from the US Department of Homeland Security seized seven items from galleries in the California and New York collections. In October, an art collector delivered another piece directly to the family.

Antiquities Man Buys Stolen Artworks

On Friday, Bragg, the New York Democrat, announced that Oberlin's Allen Museum had returned Schiele's “Girl with Black Hair” to Grunebaum's heirs. In 1958, Charles Parkhurst, who ran the Oberlin Museum and was part of the Monuments Men effort, purchased the piece, Andrea Simakis, an Oberlin College spokesman, wrote in an email. She added that it was “unbelievable” that he had purchased artwork that might have been deliberately stolen.

She said the college voluntarily redid the drawing. “We hope this provides some degree of closure for the family of Fritz Grünbaum.”

The Carnegie Museum of Art returned “Portrait of a Man” to the family. The Carnegie Institute accepted the drawing as a gift in 1960, according to what was reported by The Sun website. Expert art historians mentioned in court records.

Museum officials said in a statement that the institution relied on a finding confirmed and upheld by a federal court that the collection from which the drawing came was not stolen by the Nazis. When Manhattan prosecutors took over the case, Carnegie Museums decided not to contest the allegations and gave the piece to prosecutors in October, according to the statement.

“If we had ever believed that Egon Schiele’s Portrait of a Man had been stolen by the Nazis, the Carnegie Museums would have returned it before now to those we believe are its rightful owners,” the statement read.

The Bragg office has now helped return 10 works of art to the family. Bragg said in a statement that this achievement reflects the “tireless advocacy” of Gruenbaum's relatives.

“Let us use this moment as an opportunity to honor and preserve Mr. Grunebaum’s extraordinary legacy — a life we should never forget,” Bragg said.

Grünbaum owned 81 of Schiele's works, the art historian said in court documents. Other works belonging to him are disputed in court.

Schiele piece, 1916, “Russian prisoner of war,” remains in the collection at the Art Institute of Chicago. The Art Institute of Chicago did not respond to a request for comment Saturday.

Oral arguments in the case against the Art Institute of Chicago are scheduled to begin April 3, said Douglas Cohen, a spokesman for the Manhattan DA.

“Infuriatingly humble web fan. Writer. Alcohol geek. Passionate explorer. Evil problem solver. Incurable zombie expert.”