If you’re reading this, you’re probably not alone.

Most people on Earth are habitats for moths that spend most of their short lives burrowed, upside down, in our hair follicles, and primarily in the face. In fact, humans are the only home of follicle demodex. They are born on us, they feed on us, they mate on us, and they die on us.

Their entire life cycle revolves around munching on dead skin cells before kicking the tiny little bucket.

It depends D. folliculorum New research on humans for their own survival suggests that microscopic mites are in the process of evolving from an external parasite to an endosymbiont — which shares a mutually beneficial relationship with their hosts (us).

In other words, these mites are gradually merging with our bodies so that they now live permanently inside us.

Scientists have now sequenced the genomes of these ubiquitous little monsters, and the results show that their human-focused presence can bring about changes not seen in other mite species.

“We found that these mites have a different arrangement of body parts genes than other similar species because of their adaptation to a life sheltered within the pores,” he said. Invertebrate biologist Alejandra Perotti explained from the University of Reading in the United Kingdom.

“These changes in their DNA led to some unusual body traits and behaviors.”

D. folliculorum It is actually a wonderful little creature. Human skin waste is her only food source, and she spends most of her two-week life in pursuit of it.

The individuals emerge only at night, in the cover of darkness, to crawl very slowly across the skin to find a mate and hopefully meet before returning to the safe darkness of the follicle.

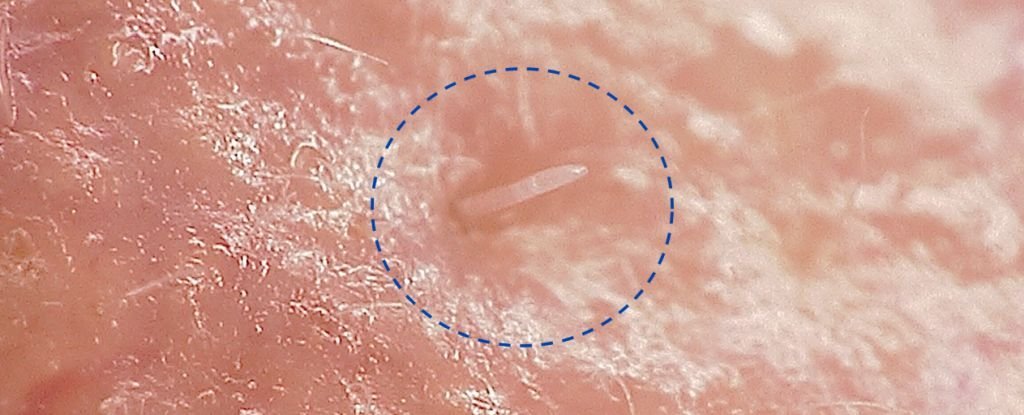

Their tiny bodies are only a third of a millimeter long, with a set of tiny legs and a mouth at one end of a long, sausage-like body – well suited to digging human hair follicles to get to the tasty labels in them.

Work on the moths’ genome, co-led by Marin and geneticist Gilbert Smith of Bangor University in the UK, has revealed some fascinating genetic characteristics that drive this lifestyle.

Since their lives are so bustling—they have no natural predators, no competition, and no exposure to other moths—their genome is down to just the basics.

Their legs are powered by three single-celled muscles, and their bodies contain as few proteins as possible, which are just what they need to survive. It is the lowest number ever seen in its widest group of related species.

This reduced genome is the cause of some D. folliculorumOther exotic picadillos, too. For example, the reason she only goes out at night. Among the missing genes are those responsible for protection from ultraviolet rays, and those that awaken animals in broad daylight.

They are also unable to produce the hormone melatonin Most living things, with various functions; Melatonin is important in humans for regulating the sleep cycle, but it stimulates movement and reproduction in small invertebrates.

This does not seem to have hindered D. folliculorum, However; It can harvest the melatonin secreted by its host’s skin at dusk.

Unlike other mites, its reproductive organs are D. folliculorum It moved towards the front of their bodies, with the penises of male moths pointing forward and up from their backs. This means that he must arrange himself under the female because she is sitting precariously on the hair to mate, which they do all night, AC/DC style (Possible).

But despite the importance of interbreeding, the pool of potential genes is very small: there is very little chance of expanding genetic diversity. This could mean that the moths are on the right track to an evolutionary dead end.

Interestingly, the team also found that at the stage of nymph development, between the larva and the adult, the mites have the largest number of cells in their bodies. As they move into adulthood, they lose cells — the first evolutionary step, the researchers said, in the arthropod species’ march to a symbiotic lifestyle.

One might wonder what are the potential benefits that humans can reap from these exotic animals; Another thing the researchers found may partially hint at the answer. For years, scientists thought so D. folliculorum He does not have an anus, and instead wastes accumulate in his body to explode when the mites die, thus causing skin problems.

The team found that this is simply not the case. Mites already have very small holes; Your face probably isn’t full of mite excrement that was expelled after he died.

“Moths have been blamed for so many things,” The zoologist Henk Brigg said from Bangor University and San Juan National University in Argentina. “The long association with humans might suggest that they could also have minor but important beneficial roles, for example, in keeping our facial pores unconnected.”

The search was published in Molecular biology and evolution.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”