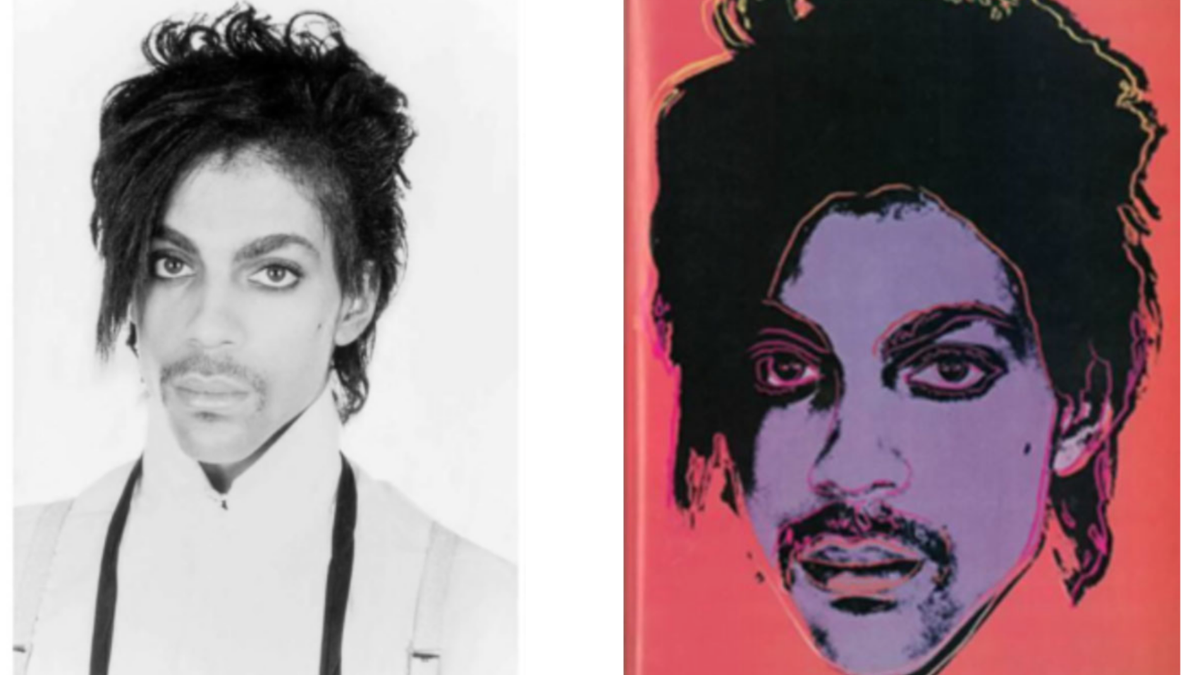

In 1981, photographer Lynne Goldsmith took a picture of the prince. Sitting alone on a white background, he wears an expression devoid of light in his eyes. In 1984, Andy Warhol used that image to create art. Warhol changed the image, adjusting the angle of the prince’s face, layering areas of color, darkening the edges, and adding hand-drawn outlines and other details in a series of 16 silkscreens.

After 40 years, the artwork is at the center of a Supreme Court case that could change the course of American art, copyright law, and even the state of the Internet. The question is whether Warhol’s work is fair use, or whether it infringes Goldsmith’s copyrights. In oral arguments on Wednesday, the court grappled with the finer points of the case, to put it mildly, it is very complex.

Did Warhol create an entirely new artwork, or is it just a derivative reinterpretation of Goldsmith’s image? If this art turned out to be derivative, the Warhol Goldsmiths Corporation would owe millions in fees, royalties, and possibly additional damages. But the implications of the impending Supreme Court ruling are a much bigger deal than a few million dollars.

Standing against it, Goldsmith says, would pave the way for artists to personalize their work without compensation, which she says would wipe out the field of photography. On the flip side, a ruling in favor of Goldsmith “would make it illegal for artists, museums, galleries, and collectors to display, sell, profit, and possibly even own a large amount of the business,” said Roman Martinez, the attorney. for the Warhol Foundation. “It would also freeze the creation of new art by established and emerging artists alike.”

Aftershocks can spread far beyond the art world, too. The issue of fair use is a major issue on the internet, and on social media platforms in particular. For example, YouTube has copyright algorithms that scan every video. If they discover a clip or music that YouTube does not have a license to use, the video will be reported, suspended, or removed. This kind of algorithm is designed to err on the side of caution, and if rules about fair use become stricter, platforms could get a lot more messed about in their decisions about content removal. Imagine the filters that bring Banhammer down on any video that has a visual similarity to copyrighted material. Sure, that would be an extreme outcome, but this is an extreme case. We are talking about the legal erasure of the legacy of the most famous artist of the twentieth century.

G/O Media may get commission

It’s an old cliché that there is no such thing as completely original art. Each piece owes something to all the art that came before it. The more you borrow from other artists, the more creative you have to be.

You do not have to pay the original artist if it is fair use, which is determined based on Four factorsThe purpose for which you use it, the nature of the art, the extent to which you use the original work, and how your new art affects the original work market. In this case, lawyers focused on the first and fourth factors, purpose, and market.

If your goal is to say something funny about an existing piece of art, you are probably in the clear. The court has already ruled that 2 Live Crew’s Take In the 1964 classic Roy Orbison Pretty woman It was fair use because it is a parody that greatly “transformed” the original work.

The Warhol Foundation argues that capturing prints also transforms the image, as it has a different meaning and message. The original was supposed to be just a portrait of Prince, but Warhol’s work was meant to be a statement about the “inhuman effects of celebrity culture in America,” Martinez said.

Chief Justice John Roberts appears to agree that this kind of shift is possible, but he has expressed his concerns. What if, asked Roberts, “I put a little smile on his face and said, ‘This is a new message’.” “The message is that the prince can be happy. The prince must be happy. Is this transformation enough?”

Many judges seemed uncomfortable with the responsibility to answer this kind of question. So was a lower court. The Second Circuit Court ruled in Goldsmith’s favor and struck down the entire question of the meaning and message of the artwork, saying that judges “should not take on the role of art critic.” The Second Circuit argued instead that the issue should focus on the “personality” of the art, which essentially means how aesthetically similar the two pieces are, and ruled that Warhol and Goldsmith’s artworks were too similar to be considered a fair use case.

Neither side seemed entirely happy with this ruling. Even representatives of Goldsmith agreed that the second circuit was wrong, acknowledging that meaning and message are two issues that the legal system must address.

For fair use, new art must not only be transformative, but be different enough that it does not compete as a substitute for original work in the art market. That could be a problem for the Warhol Foundation. Goldsmith’s photo was taken for an article on Prince for Newsweek, and Warhol’s piece was used in an article on Prince of Vanity Fair.

“The difficulty of this case is that this particular photograph is being used, probably, for the same purpose, to identify an individual in a magazine in a commercial setting,” Judge Neil Gorsuch said.

Justin Sonia Sotomayor seemed to agree, but Judge Roberts challenged the idea. “It’s a different style. It’s a different purpose. One is a commentary on modern society,” Judge Roberts said, and the other is to show what Prince looks like.

The arguments were unusually light for the court, with both lawyers and judges cracking jokes about the art world and pop culture. The faint judge Clarence Thomas noted that he was a fan of Prince, at least in the 1980s, while comments by Judge Amy Connie Barrett suggested a fondness for “The Lord of the Rings.”

But the court’s decision will have serious repercussions. A broad decision in favor of the Warhol Foundation could theoretically make it easier to steal or make free use of artists’ work. During the trial, the issue of cinematic adaptations of books received great attention. Judge Sotomayor noted that filmmakers reinterpret plots, add characters and dialogue, and make other changes that could be considered transformative, but no one argues that you shouldn’t pay an author when you turn their book into a movie.

As Goldsmith attorney Lisa Platt has expressed, the wrong ruling could mean “Anyone can turn Darth Vader into a hero or turn ‘All In The Family’ into ‘The Jeffersons’ without paying the creators a single cent.”

On the other hand, a narrow judgment in favor of a goldsmith can have huge repercussions on the art world. Real Estate Pop Art Icons Robert Rauschenberg And the Roy Lichtenstein He joined the Brooklyn Museum in a friendly brief, telling the court to uphold the 2nd Circuit’s decision, to “impose a profound coolness on artistic progress, in which the creative appropriation of existing images has been an essential component of artistic development for centuries.”

“Infuriatingly humble web fan. Writer. Alcohol geek. Passionate explorer. Evil problem solver. Incurable zombie expert.”