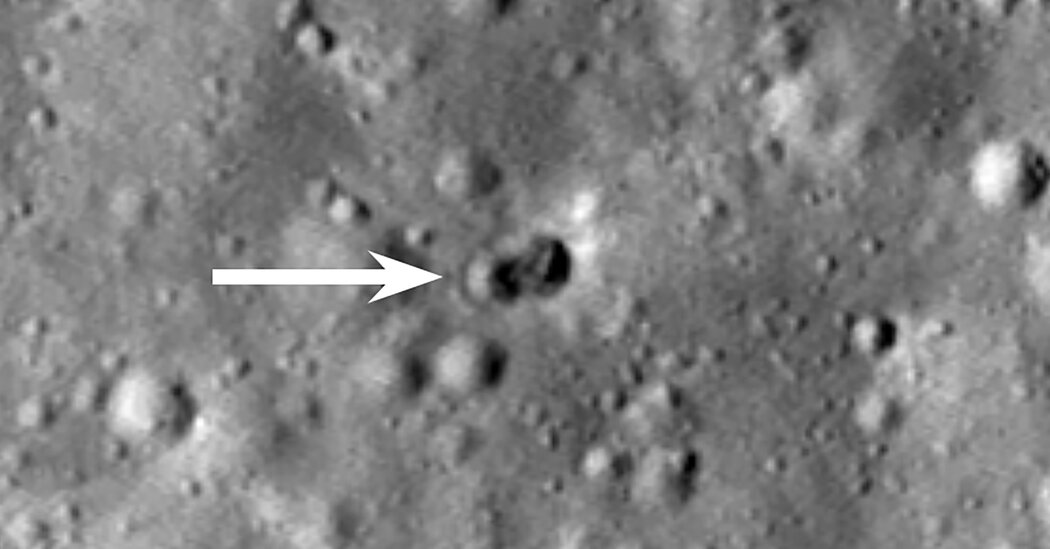

After months of sifting through images of the moon’s surface, scientists have finally discovered the site of the crash of a forgotten rocket stage that hit the far side of the moon in March.

They still do not know for sure which missile the stray debris originated from. They are puzzled as to why the collision drilled two holes, not just one.

“It’s fascinating, because it’s an unexpected result,” said Mark Robinson, a professor of geosciences at Arizona State University who serves as the principal camera investigator aboard NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft, which has been photographing the moon since 2009. It is always more fun than if the prediction of the hole, its depth and diameter was just right.”

The The missile crash plot began in January When Bill Gray, developer of Project Pluto, a suite of astronomical software used to calculate the orbits of asteroids and comets, traced what looked like the rocket’s upper stage. He realized that he was on a collision course with the far side of the moon.

The accident was certain, at approximately 7:25 a.m. ET on March 4. But the object’s orbit was unknown, so there was some uncertainty about when and where the collision occurred.

Gray said the rocket part was the second stage of the SpaceX Falcon 9 that launched the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Deep Space Climate Observatory, or DSCOVR, in February 2015.

A NASA engineer noted that DSCOVR’s launch trajectory was inconsistent with the orbit of the object Mr. Gray was tracking. After further research, Gray concluded that the most likely candidate was the Long March 3C missile launched from China a few months ago, on October 23, 2014.

Students at the University of Arizona reported that analyzing the light reflected from the object found that the combination of wavelengths matched similar Chinese rockets rather than the Falcon 9 rocket.

But a Chinese official denied it was part of a Chinese rocket, saying that the rocket stage of that mission, which launched the Chang’e-5 T1 spacecraft, had reentered Earth’s atmosphere and burned up.

No matter which rocket it was a part of, the body continued to follow the upward path dictated by gravity. At the expected time, it slammed into the far side of the moon inside the 350-mile-wide Hertzsprung crater, out of sight of anyone on Earth.

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter was not in a position to witness the impact, but the hope was that a newly carved crater would appear in an image taken by the spacecraft later.

Mr. Gray’s program made one impact site prediction. Experts at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory calculated a location a few miles to the east, while members of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Lincoln Laboratory predicted the accident would occur tens of miles to the west.

That means the researchers had to search a patch of about 50 miles for a crater a few tens of feet wide, compared to the lunar landscape before and after the impact to identify the recent disturbances.

Dr. Robinson said he worries that it “takes a year of imaging to fill the box.”

While the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has photographed the vast majority of the Moon multiple times over the past 13 years, there are a few spots it has missed. It turned out that some of the gaps were near the expected crash site.

Dr. Robinson remembered thinking about Murphy’s Law and joked, “I know exactly where it’s going to happen.”

Since the collapse was predicted a month ahead of schedule, the mission team was able to fill in most of the gaps.

Then the search began.

Usually, a computer program does the comparison, but this works best if the before and after photos are taken at the same time of the day. For this search, several images were taken at different times, and the difference in shades confounded the algorithm.

With all the false positives, Dr. Robinson said, “We just sat down and several people were manually going through millions of pixels.”

Alexander Sonek, a senior with the Arizona Department of Geosciences, contributed to the effort. He estimated that he spent about 50 hours over several weeks performing the arduous task.

Mr. Sonke graduated in May. I got married. Went on honeymoon. A week and a half ago it was his first day on the job – he’s about to embark on his postgraduate studies with Dr. Robinson as his advisor – and he resumed the search for a locus of influence.

I have found it.

Mr. Sonke said he saw “a group of pixels that looked significantly different in brightness” as the before-and-after images flashed back and forth.

“I was very confident when I saw that this was a new geological feature,” said Mr. Sonke. “I definitely jumped out of my seat a little bit, and I had a feeling this was definitely it, and then I tried to rein in my excitement.”

Dr Robinson said the eastern crater, about 20 yards in diameter, is superimposed on the slightly smaller western crater, which likely forms a few milliseconds before the eastern crater.

This is it It’s not the first time a part of a spacecraft has hit the moon. For example, it also dug up pieces of the Saturn 5 rockets that took astronauts to the Moon in the 1970s. But none of these effects created a double crater.

The reason for this person rising may indicate his mysterious identity. The Chinese mission in October 2014 carried the Chang’e-5 T1 spacecraft, a precursor to another mission, Chang’e-5, which landed on the Moon and returned rock samples to Earth.

The T1 spacecraft did not include a lander, but Dr. Robinson believes it has a heavy mass at the top of the stage to simulate the presence of one. If so, it is possible that the rocket engines at the bottom and the landing simulator at the top created the two craters.

“This is just speculation on my part,” said Dr. Robinson.

The other parts of the rocket stage were thin and light aluminum, and it’s unlikely that much of a dent on the lunar surface would.

The actual impact site is between the sites predicted by Mr. Gray and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, close to the NASA site. “It was within the margins of error that we calculated,” Mr. Gray said.

It was also fortunate that the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter team filled in the gaps – called gores, in the parlance of mapmakers – in the images. “As Murphy believed, that thing affected what was one of the unfairness,” said Dr. Robinson. “If I hadn’t been alerted, we wouldn’t have had a picture before.”

Scientists may have finally found the crash site. The dirt shed from the dug hole is usually brighter, and gets darker with time. This is how scientists identified craters caused by Saturn 5 phases.

But they’re still looking for a little bright spot in the moon’s haystack.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”