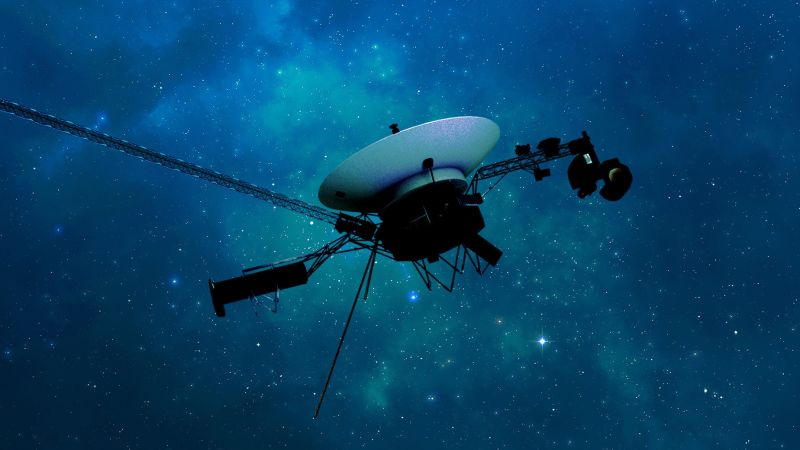

NASA/JPL-Caltech

NASA’s Voyager 1 is shown in an illustration as the spacecraft travels through interstellar space, or interstellar space.

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news of fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

—

The Voyager 1 spacecraft is sending a steady stream of science data from uncharted territory for the first time since a computer glitch sidelined NASA’s historic mission seven months ago.

Voyager 1, currently the farthest spacecraft from Earth, stopped communicating coherently with mission control in November 2023. The probe appeared stuck in a “Groundhog Day” scenario, as the telemetry modulation module in the flight data system sent out a repetitive, inconsistent pattern. Decipherable code of billions. Miles away.

A creative repair by the Voyager mission team restored contact with the spacecraft, and engineering data began They stream back to Mission Control in AprilTo inform the team of the health and operational status of the spacecraft.

However, data from Voyager 1’s four science instruments, which study plasma waves, magnetic fields and particles, have remained elusive. This information is important to show scientists how particles and magnetic fields change as the probe flies away.

On May 19, the Voyager team sent a command to the spacecraft to begin returning science data. Two of the devices responded, but recovering data from the other two took time, and the tools required recalibration. Now, all four tools are streaming usable scientific data, according to one of the researchers Update shared by NASA on June 13.

Voyager 1’s flight data system is responsible for collecting information from the spacecraft’s science instruments and combining it with engineering data that reflects the health of the probe. Mission Control on Earth, located at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, receives that data in the form of a binary code, or a string of ones and zeros.

It took some time and some unconventional thinking for Voyager mission specialists to decipher the spacecraft’s garbled code. But once they did, they identified the cause of the problem: 3% of the flight data system’s memory was corrupt.

One chip responsible for storing part of the system’s memory, including some computer program codes, was not working properly and the loss of the code on the chip made Voyager 1’s scientific and engineering data unusable.

Since there was no way to fix the chip, the team stored the affected code from the chip elsewhere in the system’s memory. They couldn’t locate a location large enough to hold all the codes, so they divided it into sections and stored them in different places within the flight data system.

There are still minor fixes required to manage the effects of the initial issue.

“Among other tasks, engineers will resynchronize the timekeeping software in the three computers on board the spacecraft so they can execute commands in a timely manner,” according to the agency. “The team will also perform maintenance on the digital recorder, which records some of the data for the plasma wave instrument that is sent back to Earth twice a year.

(Most of Voyager’s science data is transmitted directly to Earth and is not recorded.)

Meanwhile, Voyager 1 is back to doing what it does best: sharing ideas from the unknown reaches of the cosmos.

The spacecraft is currently about 15 billion miles (24 billion km) from Earth, while its sister vehicle, Voyager 2, has traveled more than 12 billion miles (20 billion km) from Earth. The twin probes launched weeks apart in 1977, and after initially flying past Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune, their mission has spanned 46 years and counting.

Both are in interstellar space, and the only spacecraft operate outside the heliosphere — the Sun’s bubble of magnetic fields and particles that extends far beyond Pluto’s orbit.

As the only extension of humanity outside the protective bubble of the heliosphere, the two probes are alone on their cosmic journeys as they travel in different directions.

Think of the planets of Earth’s solar system as existing on a single plane. Voyager 1’s path took it up and out of the plane after passing Saturn, while Voyager 2 passed over the top of Neptune and moved down and out of the plane, said Susan Dodd, Voyager project manager at JPL. he previously told CNN.

Information collected by these long-lived probes, the only two spacecraft to have directly sampled interstellar space with their instruments, is helping scientists learn about the cometary shape of the heliosphere and how it protects Earth from energetic particles and radiation in interstellar space.

Over time, both spacecraft have encountered unexpected problems and outages, including a seven-month period in 2020 when Voyager 2 was unable to communicate with Earth. In August 2023, the mission team used long-range “scream” technology to restore communications with Voyager 2 after a command inadvertently pointed the spacecraft’s antenna in the wrong direction.

“We never know for sure what will happen to the Voyagers, but I’m always amazed when they keep moving forward,” Dodd said in April.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”