NASA has unveiled full-color images from the $11 billion James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), marking the first of what is sure to be many versions of the ultra-powerful optical instrument. But even if taken alone, these five images represent a colossal feat and the culmination of a 26-year process to give humanity a more detailed view of the early universe.

The image was revealed today after the initial release of the image by President Joe Biden on Monday. That shot, called “The Web’s First Deep Field” It showed the cluster SMACS 0723, a vast swirl of galaxies that is actually just a slice of the universe the size of “a grain of sand on the tip of your finger at arm’s length,” as NASA Administrator Bill Nelson put it into a live broadcast.

Today’s discoveries include a galaxy cluster and a black hole. The atmosphere of a distant planet. the epic death knell for a distant star; and a “star nursery” where stars are born. We’ve looked at some of these targets before, thanks to JWST’s predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope, all of which have been known to astronomers. But due to the unprecedented sensitivity of the JWST instruments and their ability to see objects in the infrared spectrum, we can see these galactic shapes more clearly than ever before.

“Oh, it’s working,” said Jane Rigby, Webb’s operations project scientist, upon seeing the first focused images from the observatory. “And it works better than we thought.”

Water signs and clouds on a puffy exoplanet

Image credits: NASA

There are more than 5,000 confirmed exoplanets — or planets orbiting a star other than our Sun — in the Milky Way alone. The existence of exoplanets raises a fundamental question: Are we alone in the universe? In fact, the obvious goal of NASA’s Exoplanet Program is to find signs of life in the universe. Now, thanks to JWST, scientists can get more information about these planets, and hopefully, learn more about whether life exists on these planets and, if so, under what conditions it can thrive.

That brings us to WASP-96 b, an exoplanet located about 1,150 light-years away. It is a large gas giant with a mass more than twice the mass of Jupiter, but 1.2 times larger in diameter. In other words, it’s “puffy,” in the words of NASA. It also has a short orbital period around its star and is relatively unpolluted by light from nearby objects, making it a prime target for JWST’s optical energy.

But this is not a picture of the atmosphere of an exoplanet. It’s a cute picture of sending an exoplanet, which may be less exciting at first glance. However, this spectrum, captured by the telescope’s near-infrared imager and non-interrupted spectrograph (NIRISS), showed unmistakable signs of water and even evidence of clouds. Zipper! It’s an “indirect way” to study exoplanets, Nicole Colon, James Webb’s deputy project scientist, explained, but the telescope will also use direct observation methods over the next year as well.

NIRISS can also pick up evidence of other molecules, such as methane and carbon dioxide. While these have not been observed in WASP-96 b, they can be detected in other exoplanets monitored by JWST.

Shells of gas and dust emanate from dying stars

Image credits: NASA

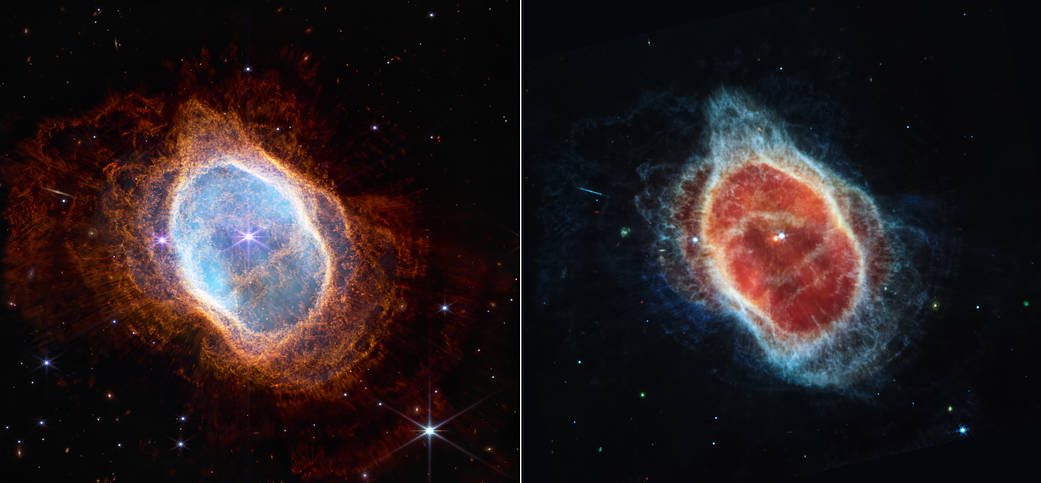

JWST also took a look at a planetary nebula officially called NGC 3132, or the “Southern Ring Nebula,” providing scientists with more clues about the fate of stars at the end of their life cycles. NASA has shown two adjacent images of this nebula, one taken in near-infrared light (left) with the telescope’s NIRCam and a second image taken with the JWST mid-infrared instrument (right).

A planetary nebula is a region of cosmic dust and gas generated by dying stars. This particular image, about 2,500 light-years away, was captured by the Hubble Space Telescope, but NASA says this updated image from JWST provides more detail on the elegant structures that surround the binary star system.

Among the two stars (best seen in the right image), there is a faint dying star located in the lower left and a brighter star early in its life. The images also show what NASA calls the “shells” surrounding the stars, each indicating a period when the fading and dying star (the white dwarf in the lower left in the right image) lost some of its mass. This substance has been expelled for thousands of years, and NASA said its three-dimensional shape is akin to two bowls placed together at their bottom, opening far away from each other.

The Cosmic Dance of Stephan’s Quintet

Image credits: NASA

First observed by French astronomer Edouard Stephan in 1877, Stefan’s pentagon shows the strange interaction of five galaxies with a degree of detail never seen before. Composed of nearly 1,000 individual images and 150 million pixels, this final image represents the largest image from JWST to date, which is about one-fifth the diameter of the Moon.

The image is a little misleading; The leftmost galaxy is actually far in the foreground, about 40 million light-years away from us, while the remaining four galactic systems are about 290 million light-years away. These four galaxies are clustered so closely, relatively speaking, that they actually interact with each other.

The image even reveals a supermassive black hole, located in the center of the highest galaxy, with a mass of about 24 million times the mass of the Sun.

I think this might actually just be heaven

Image credits: NASA

JWST also gives us a more in-depth look at the Carina Nebula, a region of the Milky Way some 7,600 light-years away. As we looked at Karina with Hubble, the new image shows hundreds of new stars, thanks to JWST’s ability to penetrate cosmic dust. The Carina Nebula reveals that the birth of stars is not a peaceful and serene relationship, but is characterized by very unstable processes that can, in some ways, be as destructive as they are destructive.

The amber landscape streaming across the bottom of the image marks the edge of the nebula’s massive, chaotic star-forming region—so massive that the highest points in this amber range, which NASA calls “cosmic cliffs,” are about seven light-years high. The data from JWST will give scientists more information about the star formation process and may help address why certain numbers of stars form in certain regions, as well as how stars end up with the mass they have.

In the end, these achievements are just the beginning. Scientists still have a lot of questions — about exoplanets, the formation of the universe and more — and they now have a powerful new tool in their arsenal to search for answers.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”