- The Chinese government is ramping up a raft of measures aimed at boosting the economy, with a key political bureau meeting scheduled for later this week to review the country’s performance in the first half.

- Rory Green, chief China economist at TS Lombard, said the immediate repercussions of a Chinese slowdown would likely come in commodities and the industrial cycle.

- Besides the immediate loss in commodity demand, Green said China’s recalibration of its key moving sectors would also have “second-order effects” on the global economy.

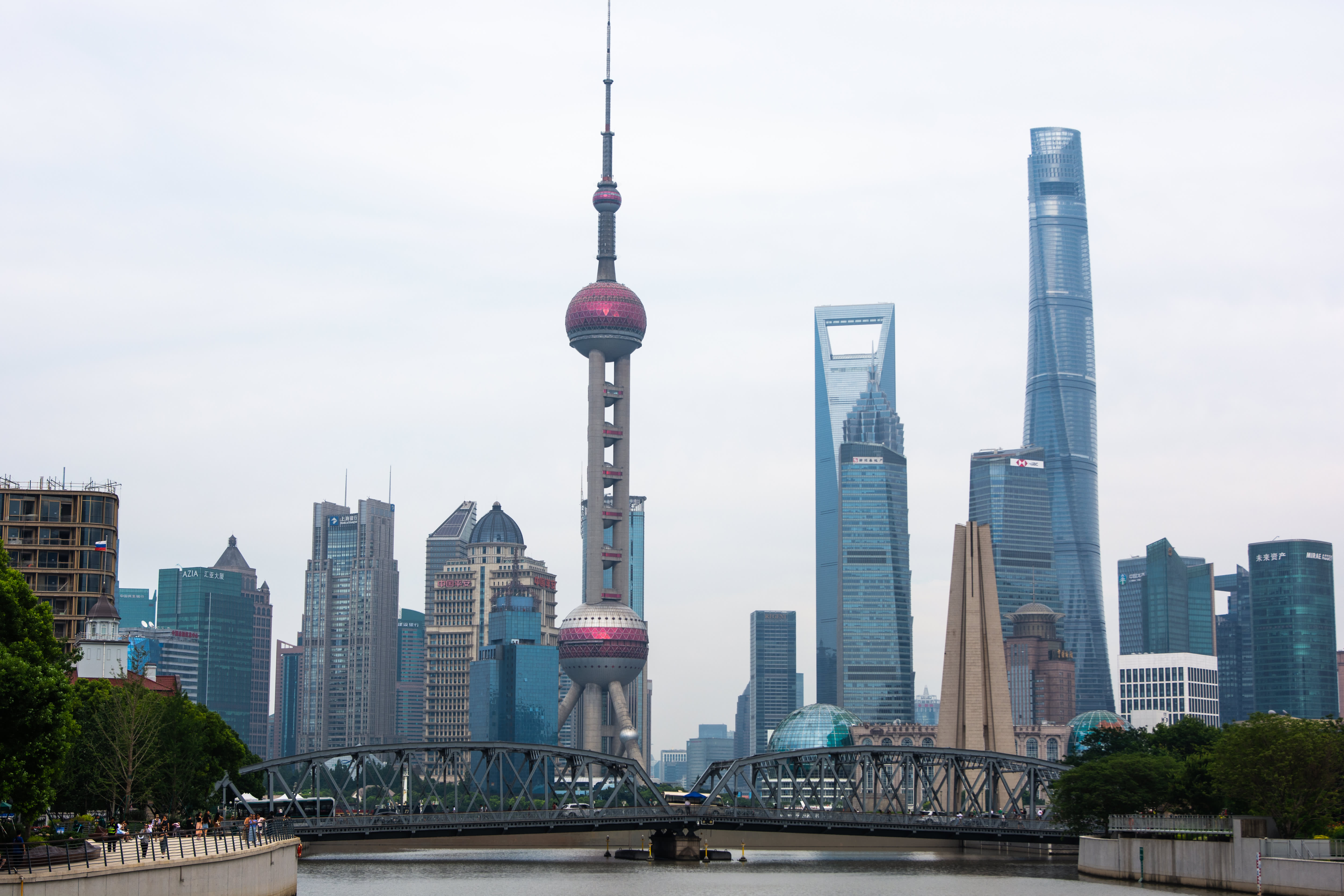

A view of tall buildings along the Suzhou River in Shanghai, China on July 5, 2023.

Ying Tang | Noor Photo, Getty Images

The Chinese economy could face a prolonged period of low growth, a possibility that could have global ramifications after 45 years of rapid expansion and globalization.

The Chinese government is ramping up a raft of measures aimed at boosting the economy, with leaders vowing Monday to “timely adjust and improve policies” for the beleaguered real estate sector, while pushing stable employment toward a strategic goal. The Politburo also announced pledges to boost domestic consumption demand and solve domestic debt risks.

China’s gross domestic product grew 6.3% year-on-year in the second quarter, Beijing announced Monday, below market expectations of a 7.3% expansion after the world’s second-largest economy emerged from strict Covid-19 lockdown measures.

On a quarterly basis, economic output grew by 0.8%, slower than the quarterly increase of 2.2% recorded in the first three months of the year. Meanwhile, youth unemployment hit a record 21.3% in June. On a slightly more positive note, industrial production growth accelerated from 3.5% yoy in May to 4.4% in June, comfortably beating expectations.

China’s ruling Communist Party has set a growth target of 5% for 2023, which is below normal and markedly modest for a country that has averaged 9% annual GDP growth since opening up its economy in 1978.

Over the past few weeks, the authorities have announced a series of pledges targeting specific sectors or intended to reassure private and foreign investors of a more favorable investment environment on the horizon.

However, these were quite broad measures that lacked some key details, and the latest reading of the Politburo’s quarterly meeting on economic affairs had a pessimistic tone but fell short of major new announcements.

The country’s leadership is “clearly concerned,” Julian Evans-Pritchard, head of China economics at Capital Economics, said in a note Monday. The statement called the economic path “tortuous” and highlighted the “many challenges facing the economy.”

This includes domestic demand, financial difficulties in key sectors such as real estate, and a bleak external environment. Evans-Pritchard noted that the latest reading mentions “risks” seven times, as opposed to three times in the April reading, and that the leadership priority appears to be expanding domestic demand.

“Finally, the Politburo meeting struck a dovish tone and made it clear that the leadership feels there is more work to be done to put the recovery on track. This suggests that more political support will be put forward over the coming months,” Evans-Pritchard said.

“But the absence of any major announcements or policy details suggests a lack of urgency or that policymakers are struggling to come up with adequate measures to support growth. Either way, it’s not particularly reassuring for the near-term outlook.”

Triple shock

China’s economy is still reeling from the “triple shock” of Covid-19 and prolonged lockdown measures, a struggling real estate sector and a host of regulatory shifts tied to President Xi Jinping’s vision of “shared prosperity,” according to Rory Green, head of China and Asia research at TS Lombard.

With China still within a year of reopening after zero-Covid measures, much of the current weakness can still be attributed to that cycle, Green suggested, but he added that these could become entrenched without an appropriate policy response.

“There’s a chance that if Beijing doesn’t get involved, the cyclical portion of the damage from the Covid cycle could go along with some of the structural headwinds that China is experiencing – particularly around the size of the real estate sector, decoupling from the global economy, and demographics – and push China into a much slower growth rate,” he told CNBC on Friday.

TS Lombard’s base case is that the Chinese economy will stabilize in late 2023, but the economy is entering a long-term structural slowdown, albeit not a Japan-style “stagflation” scenario, and average annual GDP growth is likely to approach 4% due to these structural headwinds.

Although the need for exposure to China will remain essential for international companies as it remains the world’s largest consumer market, Green said the slowdown could make it “a little less enticing” and accelerate a “decoupling” from the West in terms of investment and manufacturing flows.

For the global economy, however, the immediate fallout from the Chinese slowdown in commodities and the industrial cycle is likely to come as China reshapes its economy to reduce its reliance on the real estate sector that has been “absorbing and driving up commodity prices”.

“Those days are gone. China is still investing a lot, but it’s going to be more advanced manufacturing, tech devices, like electric cars, solar panels, robotics, semiconductors, those kinds of areas,” Green said.

“The proprietary driver—however, the pool of iron ore from Brazil and/or Australia, machinery from Germany or hardware from around the world—is gone, and China will be a less important factor in the global industrial cycle.”

Second order effects

The recalibration of the economy away from ownership and toward more advanced manufacturing is evident in China’s massive push into electric vehicles, which has led the country to surpassed Japan earlier this year As the largest exporter of cars in the world.

“This shift from complementary economies, with Beijing and Berlin benefiting from each other, to now being competitors is another big consequence of the structural slowdown,” Green said.

He noted that in addition to the immediate loss in commodity demand, China’s response to its economic shifting sands would also have “second-order effects” on the global economy.

“China still makes a lot of stuff, they can’t consume it all at home. A lot of the stuff they’re making now is of much higher quality and that will continue to happen, especially since there’s less money going into real estate, trillions of renminbi going into these high-tech sectors,” Green said.

“So the second effect is, not only is there less demand for iron ore, but it’s also much higher global competition across a range of advanced manufactured goods.”

Although it is not yet clear how Chinese households, the private sector and state-owned enterprises will look after the transition from a model driven by real estate and investment to one supported by advanced manufacturing, Green said the country is currently at a “focal point”.

“The political economy is changing, partly by design, but also partly due to the fact that the real estate sector is virtually dead or if not dying, so they have to change and a new development paradigm has emerged,” he said.

“It won’t just be a slower version of the China we had pre-Covid. It will be a new version of the Chinese economy, which will also be slower, but it will be one with new engines and new kinds of idiosyncrasies.”

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”