amount of oxygen Earth’s atmosphere makes it a habitable planet.

Twenty-one percent of the atmosphere consists of this life-giving element. But in the deep past — as far back as the modern era, 2.8 to 2.5 billion years ago — This oxygen was almost absent.

So how did Earth’s atmosphere become oxygenated?

Our researchpublished in Natural Earth Sciencesadds a tantalizing new possibility: that at least some of Earth’s early oxygen came from a tectonic source through movement and destruction of the Earth’s crust.

Archean land

The Archean eon represents a third of our planet’s history, from 2.5 billion years ago to the past four billion years.

This strange land was a covered water world green oceansshrouded in methane haze, and completely lacking in multicellular life. Another strange aspect of this world is the nature of its tectonic activity.

On modern Earth, the dominant tectonic activity is called plate tectonics, where the oceanic crust—the outermost layer of land beneath the oceans—sinks into the Earth’s mantle (the area between the Earth’s crust and core) at meeting points called subduction zones. However, there is considerable debate as to whether plate tectonics made a comeback in the Archean era.

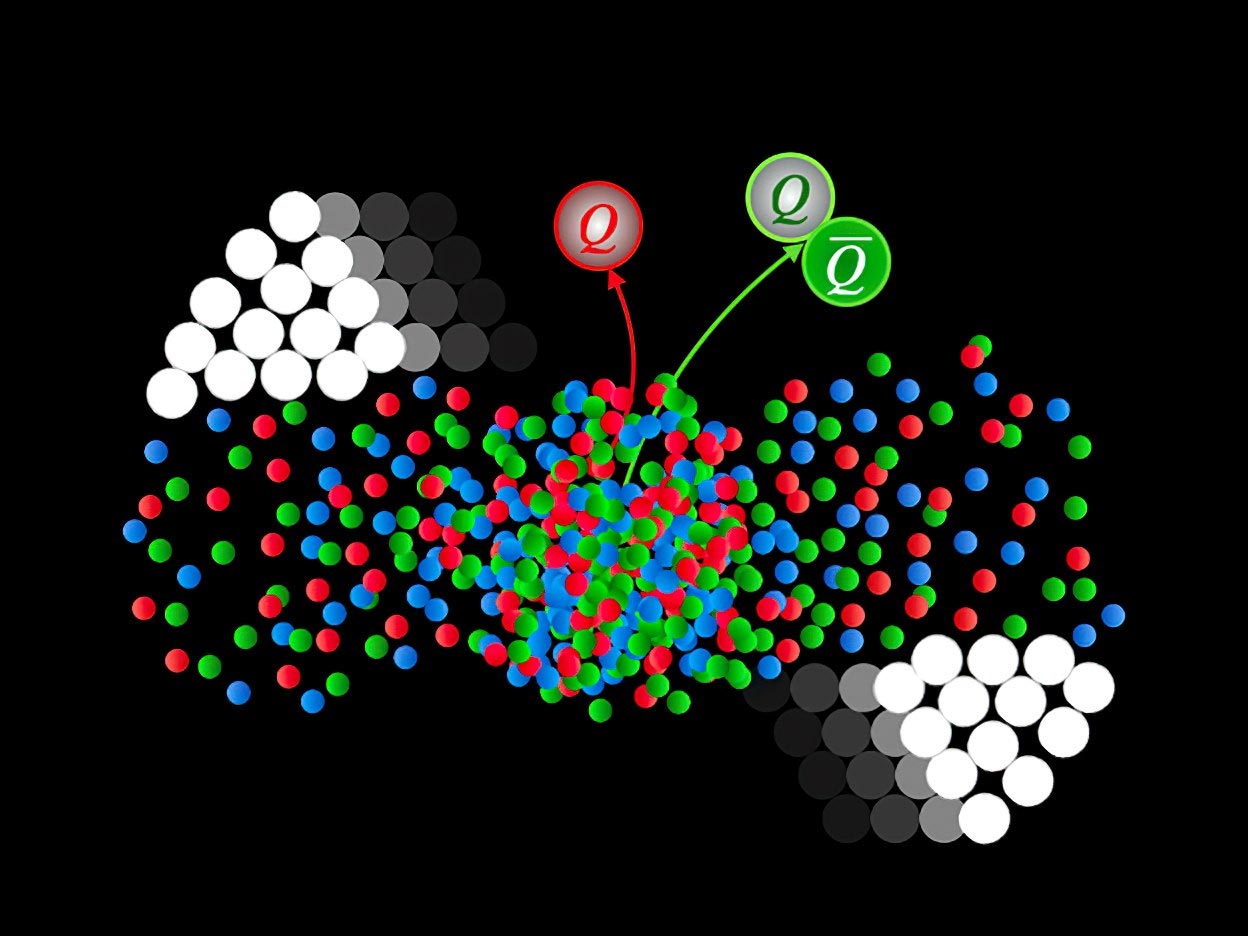

One feature of recent subduction zones is their connectivity oxidized magma. This magma forms when oxidized sediments and bottom waters — cold, dense waters — form near the ocean floor. inserted into the Earth’s mantle. This produces magma with a higher oxygen and water content.

Our research aims to test whether the absence of oxidants in Archean bottom waters and sediments can prevent the formation of oxidized magmas. The identification of such magma in new igneous rocks could provide evidence that subduction and plate tectonics occurred 2.7 billion years ago.

Experience

We collected samples of 2,750- to 2,670-million-year-old granitic rocks from across the Upper Province’s Abetepe Wawa sub-district—the largest preserved Archean continent stretching 2,000 kilometers from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to far eastern Quebec. This allowed us to investigate the level of magma oxidation generated throughout the new age.

Measuring the oxidation state of these igneous rocks — formed through the cooling and crystallization of magma or lava — is challenging. Post-crystallization events may have modified these rocks through deformation, burial, or subsequent heating.

So, we decided to take a look at the mineral apatitelocated in zircon crystals in these rocks. Zircon crystals can withstand extreme temperatures and stresses from post-crystallization events. They hold clues about the environments in which they were originally formed and provide accurate ages for the rocks themselves.

Tiny apatite crystals less than 30 microns wide—the size of a human skin cell—are trapped in the zircon crystals. contain sulfur. By measuring the amount of sulfur in the apatite, we can determine if the apatite has grown from oxidized magmas.

We managed to measure oxygen escape of the original Archean magma – which is basically how much free oxygen is in it – using a specialized technique called X-ray absorption spectroscopy near the rim structure (S-XANES) at the Synchrotron’s Advanced Photon Source Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois.

producing oxygen from water?

We found that the magma’s sulfur content, which was initially about zero, increased to 2,000 ppm about 2,705 million years ago. This indicates that the magma has become rich in sulfur. In addition, the Predominance of S6 + – a type of sulfur ion – in apatite He suggested that the sulfur was from an oxidized source, identical Data from host zircon crystals.

These new findings indicate that oxidized magmas formed in the modern era, 2.7 billion years ago. The data show that a lack of dissolved oxygen in the Archaean reservoirs did not prevent the formation of sulfur-rich, oxidized magmas at subduction zones. The oxygen in this magma must have come from another source and was eventually released into the atmosphere during volcanic eruptions.

We found that the occurrence of these oxidised magmas correlates with major gold mineralization events in the Upper Province and Yilgarn Craton (Western Australia), demonstrating a link between these oxygen-rich sources and the formation of global ore deposits.

The implications of this oxidized magma go beyond understanding early Earth’s geodynamics. Previously, it was thought that Archean magma was less likely to oxidize when it is ocean water And the Ocean floor rocks or sediments has not been.

While the exact mechanism is not clear, the occurrence of this magma indicates that the process of subduction, in which ocean water is transported hundreds of kilometers into our planet, generates free oxygen. This then oxidizes the upper mantle.

Our study shows that the Archean subduction may be an unexpected vital factor in Earth’s oxygenation, early Oxygen whiffs 2.7 billion years ago as well The Great Oxidation Event, which saw atmospheric oxygen increase by 2% from 2.45 to 2.32 billion years ago.

As far as we know, Earth is the only place in the solar system – past or present – with active plate tectonics and subduction. This suggests that this study could partially explain the lack of oxygen and, eventually, life on other rocky planets in the future as well.

This article was originally published Conversation by David Moll at Laurentian University, and Adam Charles Simon, and Xuyang Meng at the University of Michigan. Read the The original article is here.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”