Humans have lived aboard the International Space Station for more than two decades.

NASA

Just in case you had any illusions about the age of the International Space Station, Monday marked the 25th anniversary of the launch of the Zarya module. A Russian-made power and propulsion module formed the centerpiece of the space station, and the first residents arrived two years later.

In other words, some of the hardware on the space station has now been in the harsh environment of outer space for a quarter of a century. Questions about how long this phenomenon could last have become more than just theoretical questions.

NASA has been grappling with how to transition from the International Space Station for some time. There is a general feeling that, given that there have been humans living in low Earth orbit for more than two decades, it would be a good idea to hold this line.

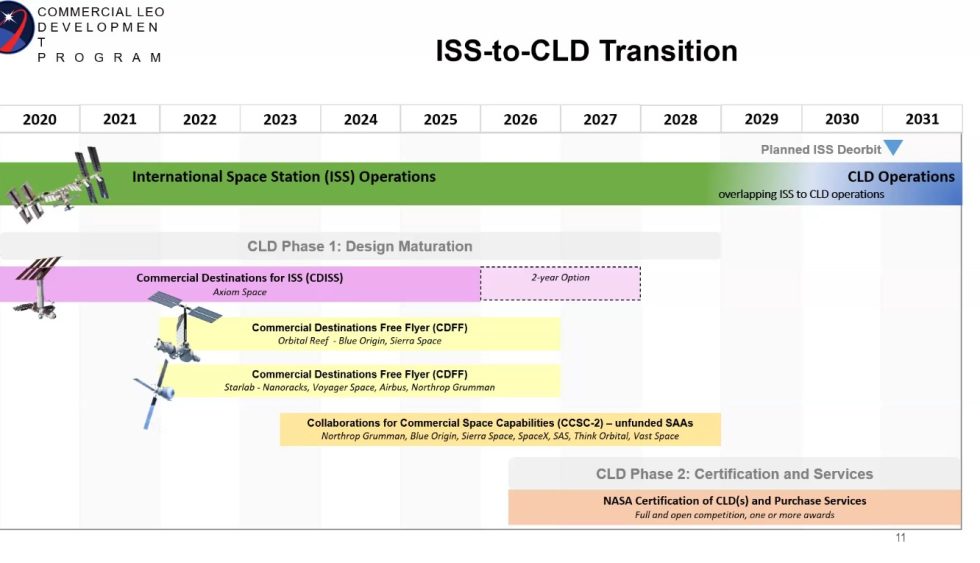

The plan NASA has settled on is to continue flying the ISS — if possible given the nature of the aging hardware and the sometimes tenuous relationship with Russia — until 2030. After that, NASA would like to see one or more private jet companies begin operating the facilities. In low Earth orbit. The agency would then rent out time on those commercially operated stations, sharing it with astronauts from other nations, as well as space tourists.

The problem is that it now seems entirely possible that no private facilities will be flying in orbit by 2030, giving rise to the dreaded “g” – in NASA parlance, gap In capabilities.

Gap or no gap

After the last manned Apollo flight in 1975, the US space agency did not have the capacity to send astronauts into space until the advent of the Space Shuttle in 1981. This six-year hiatus in human spaceflight was painful for the space agency. The process was repeated in 2011, when the Space Shuttle was retired and NASA had to wait nearly nine years for a replacement, in the form of SpaceX’s Crew Dragon.

These two gaps were caused by a combination of poor planning, insufficient funding, and overly optimistic timelines. Fortunately, it’s hard to imagine NASA facing a gap in human spaceflight capability any time soon. Not only does the agency have the Dragon spacecraft, but Boeing’s Starliner vehicle should also begin flying soon. NASA also has its own Orion deep space spacecraft. Looking further, SpaceX has a larger Starship spacecraft coming, Sierra Space intends to eventually add a crew to the Dream Chaser, and Blue Origin is also planning a crewed spacecraft. like Says the answer in Three friends!NASA will have it soon Abundance or excess From crew vehicles.

The biggest problem now is where they will go.

NASA has been planning the move to “commercial LEO destinations,” known as CLDs, for about half a decade. It has development contracts with Axiom Space, Blue Origin, and Voyager Space for three different concepts Working with other companies, including SpaceX and Vast Space, with different plans. The authority expects to award large “services” contracts to one or more companies in 2026 to support the development of private stations.

Phil McAllister/NASA

The real question is whether these options will be ready in four years. Space stations are difficult. It took NASA and a half-dozen other space agencies around the world a decade to plan, build, and launch the first elements of the International Space Station. These companies are expected to do it faster and for much less money.

Maybe the gap is okay

On Monday, during a meeting of NASA’s Advisory Board’s Human Exploration and Operations Committee, a NASA official said he didn’t want to see a gap in low Earth orbit. But Phil McAllister, director of the Commercial Spaceflight Division at NASA Headquarters who oversees the CLD program, said he could accept one if the result was a long-term solution.

“That would be bad, and I don’t want a gap,” McAllister said. “But if the CLDs aren’t ready, we might have one. Personally, I don’t think that would be the end of the world. It wouldn’t be irreversible, especially if it’s relatively short-term. That might impact some research to some extent. But we can benefit from Crew Dragon and Starliner to reduce the gap effect.”

McAllister said the two spacecraft could be equipped to allow a two-person crew to remain in space for up to 10 days to complete the necessary research.

One reason this gap is inevitable is finance. McAllister pointed to the possibility of federal budget cuts in the coming sessions as the US government reins in spending. “With all the budget challenges we have, you know, something has to give,” he said.

The US Congress has already been somewhat reluctant to fully fund commercial space stations, and it seems not unreasonable that reduced funding for commercial space stations would slow their development.

Although McAllister did not address the matter Monday, some commercial space station companies have also raised concerns about the specter of an ISS extension. If NASA or Congress pushes to extend the aging facility beyond 2030, it will likely weaken its ability to raise private capital for commercial alternatives.

“Explorer. Unapologetic entrepreneur. Alcohol fanatic. Certified writer. Wannabe tv evangelist. Twitter fanatic. Student. Web scholar. Travel buff.”